Levels of Abstraction

As the child grows so does the challenge of conveying abstract thoughts in daily communication. Marion Blank’s delineation of four levels amazingly tracks how young children, ages one to six, acquire the ability to use language to comprehend, consider, and talk beyond what they can directly perceive.

Her contribution of these levels of abstraction helps us see steps in complexity that are worth attending to as children grow up. Her sequence builds from language directly matching what a child is strongly experiencing to language merely referring to something perceivable right now.

- words that match what is already being noticed (matching)

- words and phrases that represent current perception (selective analysis)

- phrases and sentences that require a connection made in the brain to mediate content about current perception (reordering)

- sentences that attempt to connect knowledge or understanding already in the brain related to current perception (reasoning)

Learning to Play the Game

The ideas presented in this paragraph are abstract. Whether you comprehend the meaning of that first sentence or this second one depends on my ability to write, your ability to read the words, and your continued interest in constructing some kind of meaning by connecting abstractions you already have in your mind. We usually call that thinking.

We cannot see, touch, or taste this content. These words on a screen are meaningless without your interest and experience in making sense of them. At sometime in your life you learned to enjoy the pursuit of finding connections among representations you have acquired from experience. Others may not be interested in whatever blah blah is going on here and would rather do something that made sense.

People acquire an interest in the challenge of making abstract connections in their early years of learning the game of communication through languages. The essential foundation for the ability and disposition to connect abstract ideas is formed in the window of early childhood from about age 1 to 6. As children learn language in their daily encounters, they gradually come to understand ideas and relationships that connect their experiences. When the world of ideas is fun, children play.

Oh how important it is to learning a language

Ideas soon predominate the content of school. By Third Grade almost all school subjects require an ability to think about what cannot be directly perceived. If a child has had little experience playing with abstractions, academic subjects become more challenging. It’s not a pleasant experience to struggle to understand the meaning of sentences like these, especially when it appears easy to others.

If we adults knew this was going on, preschool could ensure all children—not just a few—have this ease by age five or six. We might benefit a child’s lifetime if we noticed the process of learning to connect words with perception, especially beyond the age when they learn to walk. Once children are mobile, some cultures stop including children in what adults are thinking.

Words Mapping Perception

Let’s look at learning language to represent ideas we cannot see.

Here is a striking phenomenon below. Big and bright. A young child (or a novice in English) happens to be here, too, and hears…

“Apple.”

We have a high probability that a young child understands what those sounds signify. Apple. The dominant perceptions of sound and sight match. That’s why Level I is called Matching Perception. The phenomenon grabs attention and the single word—also strongly dominant—directly corresponds. Same is true of other language learning. アップル, manzana, aporo, एप्पल, táo, apulosi, and تفاحة paired with the strong image join the comprehension game. Generally, this would be comprehendible to children around one year old.

At the other end of the I, II, III & IV scale, at the highest level, we have thinking about the current phenomena. Language is still mapping perception, but abstractions are involved in comprehension.

“You know, each seed will grow a different kind of apple.“

The meaning here must be constructed. The listener’s existing neural networks, built over years of experience, connect to the image above. The message is abstract. The future isn’t here, but the seeds are, challenging the brain to make sense of this sentence in the English language referring to this perception. Those children (or English language learners), who have had experience with apples and seeds and, most importantly, an interest in thinking about them, have an opportunity to construct that meaning. Most five-year-old children are able to participate the cognitive challenge and find it rather fun.

The meaning here must be constructed. The listener’s existing neural networks, built over years of experience, connect to the image above. The message is abstract. The future isn’t here, but the seeds are, challenging the brain to make sense of this sentence in the English language referring to this perception. Those children (or English language learners), who have had experience with apples and seeds and, most importantly, an interest in thinking about them, have an opportunity to construct that meaning. Most five-year-old children are able to participate the cognitive challenge and find it rather fun.

Since most of the work takes place in cognition rather than perception, Marion Blank rightfully called this Reasoning About Perception, Level IV, the highest level on this perception/abstraction scale.

Playful Curriculum

Those six-year-olds children, who have had experiences with apple trees, varieties of apples, growing seeds, and enjoy connecting ideas, might be amenable to the challenge of painting what might grow from those seeds. This could be fun for other children, too, an opportunity we might easily have missed.

Speaking of apple’s fruitfulness, it seems to me that differentiating levels of abstraction in early language acquisition offers more than what first meets the eye. Reordering Perception Level III and Reasoning About Perception Level IV highlight receptive language incongruities, which are ripe for engaging mental tricks to play on young children and second language learners. (The Learning Frame “Engagement”)

Beyond Perception

Beyond Level IV, we lack something to look at or see or taste. Abstractions shoot off into brain space only, without a grounding in perception. For example, nothing is here to help you make sense of these next two sentences:

It took 30 years for researchers to breed the “Honeycrisp” variety and propagate enough grafted cultivars of this popular apple. Since “Honeycrisp” trees were introduced in 1991, millions have been planted, producing excellent fruit that is enjoyed by consumers all over the United States.

Language like this codes the meaning of most texts and aptitude tests. The sentences stand alone, without any perceptual referent, so Marion Blank called these verbal-verbal abstractions, in contrast with verbal-perceptual, which her scale addresses. The levels of abstraction here are stages of learning language abstractions. Young children acquire this essential foundation gradually—over years of playing a kind of game—figuring out what people are saying while experiencing the sensations they are receiving in this moment.

Levels of Abstraction

I created a slide show to introduce early childhood educators to the Levels of Abstraction through examples rather than definitions. I remember months of difficulty trying to understand the verbal description of what made Level III, Reordering Perception, distinct from Level IV. I think it’s easier to see the distinction in images, at least at first.

You may not have encountered Marion Blank’s remarkable work, so a bit of an introduction may be useful to insert here. I have been intrigued with her analysis of adult-child interactions since I first read Teaching Learning in the Preschool in 1973. Most well known, I think, is the Preschool Language Assessment Instrument, which I used to explore competence with abstractions with many children. She and her colleagues presented their investigation results in The Language of Learning: the preschool years, Blank, Rose, and Berlin (1978). I was curious to see how these distinctions related to children in my preschools with a variety of language backgrounds and aptitudes.

You may not have encountered Marion Blank’s remarkable work, so a bit of an introduction may be useful to insert here. I have been intrigued with her analysis of adult-child interactions since I first read Teaching Learning in the Preschool in 1973. Most well known, I think, is the Preschool Language Assessment Instrument, which I used to explore competence with abstractions with many children. She and her colleagues presented their investigation results in The Language of Learning: the preschool years, Blank, Rose, and Berlin (1978). I was curious to see how these distinctions related to children in my preschools with a variety of language backgrounds and aptitudes.

As a researcher, she offered the levels as test items (more accurately called “demands”) designed to differentiate competence at each of the four levels. These were two of the three kinds of demands: tutorial questions (Why are these…?) and directions (Point to…). The tester marked the child’s performance with classification system rating fully correct, adequate, and inadequate. The child’s task was to perform as requested. To this date most of the literature on Levels of Abstraction continues to be referred to as “Levels of Questioning.” The expectation, it seems, is to “teach” children to speak abstractly by making them follow directions, not in creating an enabling environment.

Power

Directions and tutorial questions exploit a power differential: the big person demands a response from the little person in a rather artificial situation. We have a boss and and underling. In any pushing situation like this the underling has only two choices: to comply or to not comply. That’s it; there is no way out. The former could be called acquiescence; the latter could be called rebellion, which can be either active (say anything to get out of it) or passive (say nothing and hope it goes away). I don’t want to foster either acquiescence or rebellion. I would very much enjoy seeing a child show some moxie and speak the truth: “Why are you asking me? You know the answer.”

Staying Informative

I don’t wish to encourage the natural tendency we seem to have to push children to do things. If you have read other works at this site, you may have seen Enterprise Talk. The guides of Enterprise Talk offer a positive way to influence children while staying authentic and acting with integrity, so a relationship of more equality can exist in which people enjoy life and find energy in learning. The guides of Enterprise Talk disarm the negative effects of power and privilege over children. The first admonition of Enterprise Talk invites people to eliminate demands and judgments: No directions. No questions. No praise.

In presenting Marion Blank’s Levels of Abstraction, I eliminated directions and questions and restated the content as information. Statements do not require children to obey; the child simply hears the language—naturally—in the current perceptual context, which happens to be how humans (and parrots) learn language. As an educator, I care about language learning not language assessment.

In this slide show I distinguish the Levels of Abstraction in statements—information—rather than questions.

LevelsofAbstractionDownload PDF Levels of Abstraction

Language Learning Years

It’s almost magical how young children, between infancy and school age, construct connections from ordinary encounters with life and language, no matter which language they are learning. Knowing the Levels of Abstraction helps adults be aware of the relation between abstract ideas and the child’s current perceptual experience. As parents and educators we are the expert speakers, and it behooves us to attend to the complexities in the child’s receptive competence during their most significant language learning years.

You can imagine, too, how varied cultures can be across the world. Some children have rich encounters with a varied, unique vocabulary, hear complexity in syntax and varied ways of representing things, and get to participate in conversations about experience, plans, and possibilities. In some cultures the language a child hears is limited to direct perception and seldom becomes abstract. “No. Don’t do that. That’s not the way. Sit down. Get your shoes. We’re going.” (For an example, compare the Ricky and Paul conversations on the Topic Changes page.)

Participation in Idea Exchanges

As educators and parents, we may be interested in the broader world of ideas and connections and want to maximize the language experiences for our children and possibly, like me, wish to alter circumstances for children world wide. The impact of all languages (including the other expressive languages, such as music, clay, paint, dance) can be life-changing; so much opens when we become masters of an expressive medium. Oral language, our main means of communication with other human beings, acquired in the early years of life, opens or narrows opportunities and understanding over a lifetime.

Being proficient in reasoning about perception with a first or second language by age six is a key component of success in school after age nine. In Third Grade, across the world, the content of instruction becomes verbal-verbal. At that point onward academic knowledge comes in texts, lectures, maps, and images with a focus on relating one abstraction with another, as in “Why did white settlers assume the Indians had no experience or culture to value?”

Water We Swim In

Some children find abstractions quite fascinating; others, who have not had much experience with it, prefer encounters that are more concrete and practical. Schools get all children but favor the abstract over the concrete. The structures of school reward the disposition to think abstractly, often to the detriment of those children who begin with little abstract language experience but may have significant, but discounted, practical experience. When abstract content isn’t fun, children may be more likely to enjoy engagement with each other or physical activity more than they would a focus on prescriptive content. Rather than adapt school to the children, we confine children to their seats, stop social play, and force the boring stuff. No wonder the differences the children bring to school become wider and wider each year.

It seems to me that early childhood educators and parents of young children might benefit from attending to these Levels of Abstraction, so they can take advantage of daily experiences, such as a mundane trip to the store, as an opportunity to reason about perception as in the chart below. All this, of course, takes practice. So here you go.

Practice

Here’s a second slide show using only one image of firefighters to challenge you to see the distinctions in levels. It’s multiple choice, which can be difficult at first. I have intentionally made this slide show difficult, because you can go back and forward again to see the subtle differences. Tasks in the zone of proximal development always flirt with levels of incompetence.

Level III was the most difficult for me to grasp.

Download PDF Abstraction Task

Commenting at Levels of Abstraction

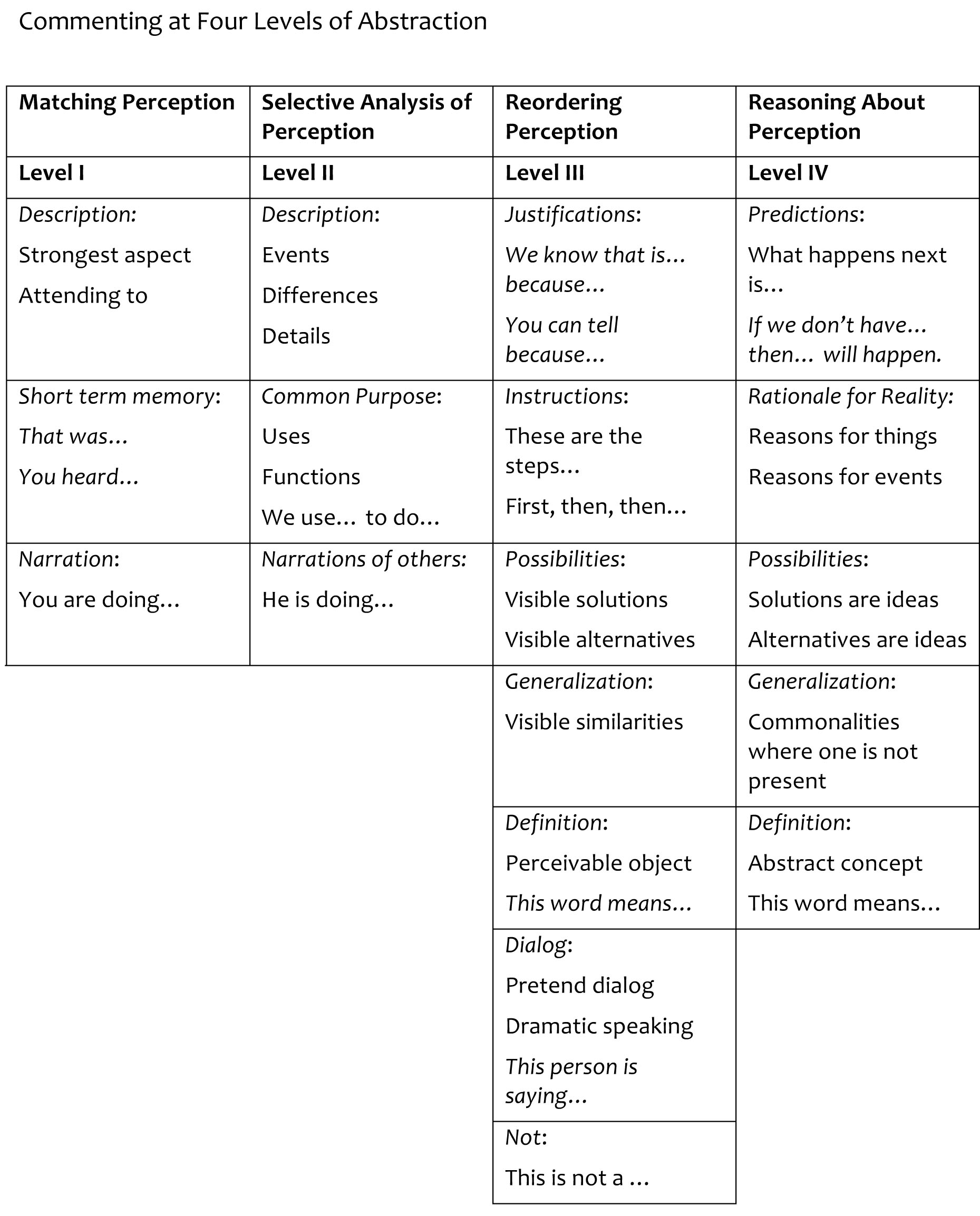

Commenting is cool, so is reading great literature to children. Input matters. When done well, careful talk and great books can provide language in the zone of engagement appropriate to their capabilities. To help with the challenge of generating cool comments I offer a chart that relates commenting and describing to the four levels of abstraction, eliminating all demands.

Organized with comparative boxes side by side, one can consider the distinctions between Level III and Level IV.

For example, if I were to make a Generalization statement at Level IV about the apple seeds, I could say, “Those apple seeds are like watermelon seeds, but rounder.”

Using Possibilities at Level III, I could say, “I want something to put the seeds in to save them for tomorrow.”

(At Level III as long as containers are visible; if nothing is around and only the child’s mind has the ideas, it’s Level IV.)

List of Comments

Here are a variety of comments at each level. This way alternatives are organized by the age when such comments are understandable for most children.

Matching Perception — Level I

Describing the strongest aspect of perception:

All gone. Truck. Here’s some milk.

Labeling a strong event that was just experienced:

Fall down. Oh, big one! Bell. Barking dog.

Narrating an action as the child is doing it:

Jumping! You dropped it. Splash.

The language is especially simple and brief, like addressing children ages 1 and 2.

Selective Analysis of Perception — Level II

Describing events and details:

—The bubble is floating higher and higher. It has blue edges. It popped in your hand!

Pointing out differences:

—These are Velcro straps and those are buckles. That one is darker. That’s navy and that’s royal blue.

Describing the common use for items:

—The cap keeps the pen moist. This boot jack helps people remove big boots.

Narrating what others are doing:

—She is climbing the ladder. Mark just returned the scissors to the rack.

Vocabulary and syntax become increasingly elaborate, like addressing children ages 2 and up.

Reordering Perception — Level III

Describing sequences or steps of a procedure:

—First we open the box; then we take out the parts; then we read the instructions.

Citing the evidence for an observation:

—You can tell this is a backhoe, because it digs by pulling the bucket back toward the cab.

Describing a visible solution to a problem:

—Over there are pins or tape you could use for that.

Pointing out what is the same about objects:

—Her tower and your castle both have three levels.

Defining what a concrete object is:

—A marker is a pen that draws wide lines or easily fills an area with color.

Offering dialogue or pretend dialogue:

—This man says, “No way am I going to eat that!”

Pointing out what is not:

—Bats and balls are not being used today.

Each refers to something present but requires one to consider it in a language-mediated way, like addressing children age 3 and up.

Reasoning About Perception — Level IV

Predicting what will happen:

—The water will flow under the carpet and soak the carpet pad.

Providing reasons for the way things are:

—Light switches are near doors, so people can turn on the lights as they enter the room.

Offering solutions to a problem that are not visible:

—Another way to build that would be with sticks and tape, which we don’t have today.

Pointing out similarities with something not visible:

—Kneading the play dough like that reminds me of when I make pasta.

Defining what an abstract idea means:

—A “courtesy” is something one says or does in kindness to everyone, no matter if you know them or not.

Each relates mentally represented experience to current perception, like addressing children age 4 and up.

Expanding the Opportunities

In some cultures abstract ways of talking to young children are daily experiences from infancy; it’s how people relate. It is much more common for children to never be talked to in that way. If you grow up without, you tend to continue that way of being. If you think facility in the abstraction game is important and a child’s home culture does not talk to their three- and four-year-old children at Levels III and IV, here are things you can do.

Vocabulary Inundation at Level II

The first place to start is at the foundation. I found remarkable benefit from making an effort to provide unique and uncommon vocabulary at Level II, Selective Analysis of Perception, pertaining to what a child was directly experiencing at that moment. For many things I encountered with my child in daily life, I didn’t have the full vocabulary. If a child was interested in talking about firefighter pictures, I had to learn all the words for fire fighter clothing and equipment. The same learning curve happened for all the words for types of heavy equipment (recently learned the word breaker for destroying concrete). It happened for the fruit and vegetables in the produce section and for urban traffic (I learned about stoplight timing, signal controls, and platoons). Most of the time, I simply asked people who worked in occupations my children were interested in what the names of things were and the verbs used for the actions. I bought used copies of What’s What a copy for home and 6 copies for school. I worked at providing all the vocabulary I could for everything my children were interested in.

One great thing about being a college instructor was being able to make people practice what is good for children through course assignments. This uncommon vocabulary task, which you can try, too, was one that many people found revolutionary:

Pick one activity or one activity area in your classroom and develop a vocabulary card for it, listing the correct name for every item, the parts of key materials, and the uncommon verbs that pertain to what the actions are. Laminate and post.

I have seen, for example, how casually naming the ferrule of a paint brush altered how children cleaned the base of the bristles. Play changes, too. I have seen a different dynamic when the vocabulary of unit blocks is provided: quad, double, unit, half unit, ramp, lintel, beam, cribbing, foundation, overlap, frame, strengthen, extend, surround, stable, balance, symmetry, interconnect, align, distribute, etc. The children gained words to talk to others about what they were doing to their friends, and it seemed to stimulate new ideas. Words influenced their designs. Words influenced problem solving. Words influenced relationships. Words enabled planning and possibilities, which are at Level III and Level IV.

Great Literature for Level III and Level IV

Great literature allows children to figure out Level III and Level IV connections from repeated readings. Treasured picture story books have lasting value often because they are constructed to enable children to understand abstract language. Redundancy and repeated readings connect ideas. Comprehension of the text is relating the pieces of the whole. That’s the purpose of re-reading books.

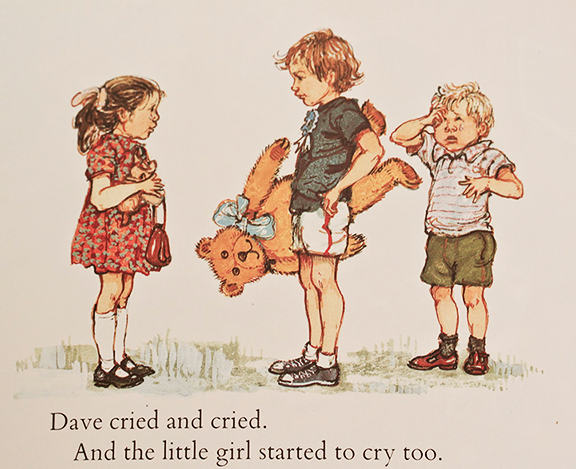

Dogger or David and Dog by Shirley Hughes is an example of the kind of book with lasting value that I am talking about. I found this image online, so I assume I can post it here as fair use. This image can give you an idea of how this book builds connections and reasons for things at Level III and Level IV.

This image is the book’s climax. The girl on the left has Dave’s Dogger she bought fair and square at a fundraiser days after Dave had lost it. The girl in the middle is Dave’s older sister, Bella, who has just won a huge teddy bear as a prize. You can see the text is at Level II, Selective Analysis of Perception: it describes only this image, as well it should.

The connections a reader has with the events in the rest of the book, before and after this picture, give the image its full meaning. I think you can imagine the listener’s brain whirling around, connecting all the pieces. Dave crying, Dave’s family searching, Bella’s bed crowded with stuffed animals so she couldn’t fit the new big one in anyway, and the resolution that follows. Children slowly construct their own understanding of what is so clearly depicted in Shirley Hughes’ illustrations and the story arc. They can then discuss emotions and loss in their own lives, too, at Level IV, if they wish.

Stories are uniquely powerful: the emotions engage us and adventure connects events, unlike any other form of expression. Just as years of research findings have shown, reading or listening to great children’s literature is a key reason children who are read to a lot have the disposition to enjoy abstract ideas.

A lending library could help parents to make sure their children spent time with each Caldecott Medal book appropriate for the age of their child. It also might help pull children away from screens. An understanding of the Levels of Abstraction also might help educators evaluate the books they use and seek to provide the best ones for their children. Often the books I see in preschools and child care spaces are leftovers. Gotta get the gems.

My Personal Proof

In a state-run program for low income four-year-olds, I pre and post-tested six children in my class whom I was most curious about. I have the hard data. Between November and May, six months, these children made an average of 1.5 years growth in abstraction as measured on Marion Blank’s Preschool Language Assessment Instrument. My point is that growth in competence here can happen quite quickly when children are between two and four years old. Reading books is probably the most direct way. The other rich path is through Step Chart Activities, since the charts are abstract and the actions concrete.

Small Group Activities for Level III and Level IV

In the Small Group Activities section I present four kinds of opportunities for regular meetings with groups of 4 or 5 children where children naturally become engaged and gain courage to participate at these higher levels of abstraction. It is learning to play the game that many children don’t experience at home. Note to language teachers: These are also highly engaging activities for students learning to speak a new language.

Picture Story Books presents a method of reading books to young children in small groups specifically to do this in a school, The Eliciting Method, which has been hugely successful for bringing the more silent children to the forefront of language participation in any language they wish to learn. I guarantee this method will out-perform any other book-reading system in the literature of early education academia.

Natural Progression Activities use silliness to challenge children to convey in words what they already know about sequences. As you can see in those videos, they almost shout in excitement at Level III Reordering of Perception.

Transformation Activities present a visual change from one state to the next—for example, what happens to bagels when they are toasted. Appearing contrary to what I have said above about demands, in this context, in a routine they come to understand as a game, the leader asks two kinds of tutorial questions: Level II (What is happening? What do you see?) and Level IV (What will happen? What will it look like?). When experienced once a week, children become careful observers and participators in predictive discussions in all areas of their lives.

The Walkabout puts everything together at once in mini field trips, indoors or out, that in my experience children treat as their favorite day of the week.

Reflections From Students

Enhancing complex commenting takes me out of my comfort zone, but, oddly, that mental challenge makes me want to get to know the kids better. I want to do more in-depth observation and have more consistent communication. The more I know the more I can get the books, songs, props, or whatever that interests them. I know about five of the children’s passionate interests, but there’s twenty-eight children in my class. I have to seriously step up and find out who these people are, then I can research the words and find the great books that fit. I have a whole new respect for children’s book authors who get it right. — Gloria Melendez

Jonathan was building with blocks. He put a small figure dressed as a chef, which he called Captain, on the shelf and began building around him. He told me the shelf was an island and the carpet was the water. I used this quiet time to try to add more unusual vocabulary: ramp, for the long block that sloped down from the shelves to the carpet; cylindrical, describing the block he picked up; columns, which supported an arch over the ramp; elevate, which he did when Captain couldn’t fit under the arch; dock, where he said the boats come; prow, for the triangular block I put at the front of the boat we were building; symmetrical, for the structure after he put quads on either side of the ramp, and asymmetrical, for the parts of the structure that didn’t display symmetry. This attempt has pushed me to type up and laminate a list of uncommon vocabulary for the block area, so that I can more fluently talk about the different structures the children create and the ways they build them. I also have to work on commenting with more Level III and Level IV making connections between present objects and circumstances not present. — Patrick Durbin

Now I really understand the importance of vocabulary enrichment. It gave me another gift to offer the children. The joy on a child’s face when a new word is learned is precious. — Nancy Awamura