Stewardship of Play

Play

As you probably know, early childhood educators enthusiastically agree: the best emerges when children play.

“Play causes the wiring in our cortex to form, the neural pathways that determine how emotionally stable we’ll be and how easily we’ll learn.”

This quote from The National Insitute for Play ought to flash in neon lights how essential play is to neurology, learning, and adjustment. If you like, you can view the gathered wisdom at their website. The NIP mission statement is spot on: “…dedicated to advancing society’s understanding and application of play — a long-ignored biological capability that can lead to healthier, happier lives.”

This natural, biologic capability of human beings usually never has a chance to grow and flourish. For many, play has been relegated to the margins, and, in some places, intentionally squashed. It’s rather sad. Once children begin to walk and talk, the conditions that optimally grow their brains fades away. It’s a loss for the creativity of homo sapiens as a species.

If play is indeed a biological capability, in the nature of human beings and essential to people’s learning and adjustment, why are opportunities for play so rare in schools and work groups?

This Stewardship of Play page presents how we, as leaders and caregivers of young children (and working groups), can act in unison to create the provisions for optimal human actualization. As of yet, we haven’t established much agreement on how to do that.

Agreements Needed

Even when we know play is good for children and work groups, it’s not clear how to foster the growth of play. We can’t just start playing ourselves, since we are the providers not the players. We can’t build it directly, and unfortunately, we may not even mean the same thing when we use the word play.

Play is an abstract idea. We can’t point to it like we can point to a dog, so we lack an easy way to know if we are referring to the same thing. We do have lists that differentiate play from other kinds of activity, which is helpful, but descriptions don’t define what is occurring or serve as guides to create play settings or to suggest what to do or how to respond.

We may read that we are to “encourage” play, but what does that mean? What are the conditions under which play grows? What sets it free? How does it start? How does it evolve? What do we do to sustain it? How do we keep from ruining it?

Stewardship, the careful and responsible management of what we have been entrusted with, addresses those seven questions.

Stewardship

Stewardship of Play is the careful and responsible leadership and care of environments for well-being, belonging, and joy. Our clients, the children (and workgroups) do their growing and do their playing without much action from us. We are leaders, watching closely and trusting them, even when at times it may not look very good.

What follows below is a story of creating a shared, actionable understanding of play and how to nurture its growth. You will find a process of generating the necessary agreements about the phases of growth, the conditions it needs to emerge and sustain, and the guides for a facilitation. Over a period of 18 years, a group of approximately 500 early educators investigated play in order to revise traditions and alter reflexive habits which hindered and even crushed it.

Socially-constructed Reality

I taught a course called Program Planning at North Seattle College in which I addressed the breadth of conditions necessary for a good school or care setting for young children. Unlike any class I ever took in my education, I thought the participants could learn more from each other than a book. I built the course for them to construct agreements and apply their conclusions to the settings where they worked. We worked for clarity in expressing our understanding until we had agreements that were acceptable, at that point in time, and then checked on how well they worked in their lives with children.

The participants in the course who did this work were from different backgrounds, cultures, and spoke different languages. Our program in Seattle was delightfully diverse, and almost everyone was a parent or currently employed working with preschool children. I set the agenda, compiled, and printed out their work. I tried to ensure that every voice was heard, for often the quieter ones opened new doors for us. I began teaching this course after 17 years teaching preschool, using video recordings and data to get better, but until I taught this course, I didn’t think I understood the big picture. When I first structured the course to rely on group learning, I had little idea what would result.

Action Research

Research approached this way, built and tested by the educators themselves, may be an unusual practice in higher education, but it makes perfect sense to me. When research is conducted and conclusions are reached by those who directly operationalize their findings (they immediately change what they do), we have research that matters. Those who know and love the children are naturally eager to do well by them. When each socially-constructed conclusion is actionable, each person who participates in that meaning-making conversation has a natural interest in testing it out. This is the opposite of being “trained.”

This process created the definition of play you will find below and derived the conditions under which that state of joy flourishes. Wave upon wave of early childhood educators constructed these lists of understandings, refined them over time, and applied these guides to grow play.

- The necessities needed for good spaces and rich opportunities for play,

- Observable indicators of involvement or lack of involvement by the players to provide the feedback for alterations if necessary, and

- Specific actions facilitators take and mistakes they avoid, so play has the conditions it needs and builds what we value for the players.

———Preamble———

Children Play Naturally

I know from experience, and confirmed by many others, that if we let children go free, let them out of the cage, with their peers of various ages and abilities, sufficiently sustained by water, bananas, and maybe a sandwich, they play powerfully day after day with strengthened spirit and self-confidence.

Those conditions of my childhood, of course, have been severely constrained in schools and care in our interest in safety, but that play was powerful. Today a world-wide movement strives to correct the absence of play, because we have overwhelming evidence of its benefits for children and communities. Opportunities for play optimize life. Play can change the world.

Before we can fix this, we have to have a shared understanding the concept of play. That’s the beginning, and we have to do that work. Brains work better together.

An Invitation

At this point, I’d like to acknowledge our common interest in play. We recognize the facts that play grows brain wiring as well as a sense of self confidence. We also are probably on the same team of advocates for children and wish to spread the good word so more and more people around the world are able to create the conditions for play for every human child.

In that spirit, I invite you to include one or two others and make this study cluster. You could, if you chose, invite others to read through the sequence of encounters below rather than read on alone. If you are able, you will probably learn more from them than you will from simply receiving a bunch of words. That’s always been true in my years of teaching. Students have told me many times that the discussions with each other were the most memorable part of the classes..

Reading is receptive not active. It doesn’t have enough activity to build deeper understanding. Pushing on alone, in the hope this will be good for you, is like watching a game from the bleachers. Discussions are like getting down on the field with others and playing.

I imagine you could read a section together, or several, and pause when you wished to discuss it. You could do it remotely, too. You could agree at the beginning, that your purpose was to talk, not just read, without a need to hurry. Listening to others and hearing yourself talk makes your brain work harder than it does alone.

Challenges appear now and again in red.

Journey Towards Understanding Stewardship

Stewardship, a tending to the conditions for play to flourish, requires first looking at what we mean by play. The common discourses are often diverse, and, from what I have seen, haven’t begun by defining what we mean, much less address how to establish the best conditions for it to grow. We have lots of use of the word play without assurance the word refers to the same thing.

Children learn through play.

Work is different than play.

Play is a process not a thing.

I want my child to learn not just play.

I don’t see any learning going on here: they’re just playing.

Guided play gives focus on specific areas of education.

Unstructured play lacks meaning.

Play builds resilience.

We need more play in schools.

I don’t see a common thread of understanding.

Play as a Concept

Play is an abstract concept. Right there we have a problem. It’s important to recognize that despite our best efforts to explain, understandings can’t be given to other people. We can’t give our dendrites. We each build our mental constructs through mental activity that connects and represents experiences.

Take dog, for example; it’s a concept, a concrete one, to get the idea. You can point to a dog. You can look up the word dog, too, and find an agreed-upon clarity: “a highly variable domesticated canine.”

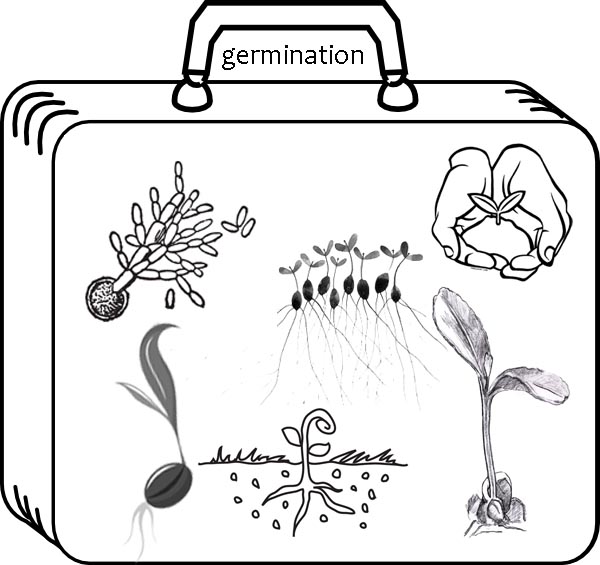

Imagine you are a child and an animal walks by on a leash, “That’s a dog, honey.” “Don’t pet that dog.” A concept is a suitcase containing representations of thousands of experiences of the physical form. Dog represents them in a word. We hold the handle with the word dog: the word we use to carry it. The handle of the suitcase says “Dog.”

If you look up the word play, you get a mess, because it is an abstract concept you can’t really point to. My English dictionary fills a full page and a half of tiny print with variants on how that play word is used. Abstract concepts refer to a set of ideas beyond a physical form.

We can use the word play, as many have, but it’s a handle on a suitcase of possible meanings. There’s no way to know if two people have the same thing in mind. Shared agreement on meaning has to provide a solid foundation for people to cooperatively create conditions for children or working groups. Our actions have to have a shared goal and an agreed visible presence in order to tell what works and what does not. Stewardship needs an agreed-upon physical result.

When I tried to promote play…

The adult role in enhancing children’s play has been a major question for me from the beginning of my work with children.

- If I played with the children, they focused on playing with me. If I let them alone, some of them played with each other. Others played alone. Others did nothing.

- When I videotaped teachers being with children who were playing, and we discussed this in class, will still could find little clarity as to our role.

- To research this further, we removed all the teachers and let the children have free run of the space. We watched the children from an observation room behind one-way glass, and the children played for half an hour. Nobody seemed to notice we were gone. Every child was engaged. Playing.

- We found in our class discussions that, in general, our fondest play memories as children occurred when no adults were present.

What should adults do to foster the optimal conditions for play? It seems to me this is a central question early childhood education.

What do you and your mates know about how to do it? Successes? Problems?

I just picked up a curriculum book from my shelf here and looked through it for how to create the conditions for play. Then I did a search online. I didn’t see work like the story below, uncovering what I know to be deep and durable understandings about the stewardship of play.

I would like to take you through a course of events where participants built a concept of play as a foundation for providing the best possible experiences for young children.

Removing the players

We have, in play, the foundation of human synergy and creativity. We know it from the inside when we are in it. Experiencing play is simultaneously fun and spiritual. Facilitating the existence of play in others is something entirely different. For someone on the outside, it is difficult to see what’s happening in others, so it’s difficult to comprehend how to help it grow. We have to build together what to look for, removing the players and examining the environment.

Over the years of exploring the teaching of this subject I have discovered that just as children construct their play from their here-and-now, influenced by the social dynamics of their playmates, learning teachers learn best by constructing their understanding of play themselves in cooperation with others. Once we have a shared understanding, we can address, in a similar fashion, the touch points of giving it means and opportunity.

Co-construction of the Concept of Play

The first day of the first course in our early childhood program, I invited participants to begin an investigation of the concept of play by playing. I offered them tubs of my large set of Cleversticks (any open-ended material can work, but this is the best one I have found for adults) and invited them to play for about 12 minutes. That was it. Simply play. Go.

The first day of the first course in our early childhood program, I invited participants to begin an investigation of the concept of play by playing. I offered them tubs of my large set of Cleversticks (any open-ended material can work, but this is the best one I have found for adults) and invited them to play for about 12 minutes. That was it. Simply play. Go.

As they played, I video taped as many people as I could right at the very beginning — the first two minutes of play. Some grabbed a bunch out of the basket, some grabbed two and stuck them together, some watched, etc. About 3 minutes later I again taped the same people. At about 8 minutes in I taped again, but this time focused on the social dynamics in various groups. When the timer rang, they cleaned up, and I prepared my video for playback.

I invited them to write for a few minutes what happened in their play. What they did first, next, next, etc., which they then shared in small groups. After sharing I called everyone together, I led a discussion to compile on a whiteboard what we could describe about play. As we progressed through the general course of events, I played the segments of video recordings from the beginning to help them recall the beginning and to see what others had done at that time. After we got the beginning of play described, I showed them the middle. After that was up I showed them the last section which was full of animated, cooperative work, and chatting.

I present now a compilation of what generally resulted from those discussions, using the documents I have kept from an estimated 500 people. Altogether, A, B, and C define play.

Synthesizing a Concept of Play

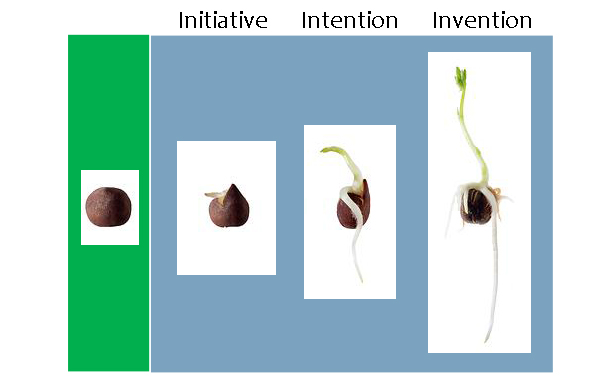

Conditions are in place for play, just like a seed has to have the right temperature and moisture. We cannot see the biochemical reactions inside the seed coat as it is hydrated. Essentially, all we can see is an environmental green light.

Usually, groups have a discussion about whether the play begins when thinking and watching starts, before movement occurs. Since we were working on a definition of play that is observable, we agreed that play we can’t agree play starts until an action starts.

The first thing we see when a seed grows is the radicle.

Initiative. Radicle emerges. In a seed, the beginning tip of the root is usually the first sign of emergence.

Play begins. In the videos, people sponteously pick up something and do something with it. It looks impulsive, a whim—sometimes with energy, like a spark. and sometimes with bored reluctance.

Intention. Seedling. The energy fuels growth in a direction, just like roots and a sprout seek nutrients and light.

A plan, a thought, or intention focuses action. A player decides to make something happen. Could be collecting the blue ones or attaching as many sticks as one can to a ring, a necklace, or something tall.

Invention. Growth. If we imagine a seedling in leaf, light energy fuels growing roots and additional leaves. Life has strength; it’s not so fragile. The plant gains strength rapidly, if conditions are right.

In describing play, a continuing series of problems arise. The discrepancy between what the materials at hand can form and the mental intention present a series of challenges.. In the video recordings, people struggled to make their structures stable or how to get parts to move correctly or make something look like what it’s supposed to be. Usually early results fail to match the early vision.

A choice players had were to keep going to make it better, adapt the intention to the constraints, or change the idea.

Once it’s looking right, invention is visible, the work becomes embellished, elaborated upon, refined, and, if conditions are right, others have ideas that contribute to that end. Play has momentum.

Emergence

Pictured above are three visible, ordered phases in play: initiative, intention and invention, which I propose can serve as nomenclature for play stages sufficient enough to engage in research and apply in practice, unlike the play suitcase you saw above. To signify this step in clarity, forward into the future, I bold and capitalize the word Play to signify a living process, with emergent stages we can study inseparably from the conditions in the environment.

Germination, as abstract an idea as play, has been foundational to plant science; nursery propagation and farming simply know they are describing a concept that includes change interlocked and interdependent with environmental conditions. If conditions are right, a healthy plant emerges. Growers have passed forward their experience from prehistoric times. They have shared their discoveries through generations about what to provide, when to provide it, and the what to do to enable the genetics to unfold. We could find ways to pass forward our experiences in stewardship of Play, in a similar way.

The concepts of Germination and Play have more than a metaphorical similarity. The more we recognize parallel emergence idea, the more we learn of its stewardship. Instead of having a wonderful but vague idea floating about, we can see Play fused to germination. Both are tender, vulnerable beginnings of growth unfolding in nature. Care.

What comes to mind?

Germination

Play has an ordered, biological, and natural sequence. We don’t have to convince anyone to get it to work or to make it happen. It arises from with each of us, given permission and opportunity.

If we have agreement that Play evolves within a narrow set of environmental conditions, and if we have agreement to attend those phases, we can figure out how to care for its growth. We are not focused on the players anymore. We don’t try to fix the seeds.

What ultimately matters is what we do and what we don’t do. The specifics of care. We provide the conditions, like nutrition, water, and light; we are the ones whose duty it is to identify what hinders or impairs Play, especially as a seedling! It can die.

Examining the Conditions

With this in mind, I’d like to return to the experience of many groups of adults who constructed these germination agreements.

The participants had much to share from their notes about their playing experience in class. Conversations with their mates about the social events were quite energetic. List A became the germination phases. List B became a list of the comments that led play forward in energy. List C was the other stuff that came up that were not so good. I listed their comments pertaining to conditions on separate whiteboards.

Over here are positives. Over here are negatives. These are the collections.

Positive Social Forces, list B

- Conversations start up in a new way.

- People comment on what others are doing.

- People laugh more.

- We get to know others because people are doing something together that is more naturally spontaneous.

- We come out of our shells.

- It’s fun and goofy at times.

- This relaxed conviviality spreads to others.

- It gets loud.

- We are watching what others do.

- We copy interesting ideas.

- Seeing what others are doing is fun.

- Having others around helps generate new ideas.

- It’s nice to hear positive comments about one’s own work.

- Their energy extends the play longer and makes it more interesting to continue.

This positive energy feeds and sustains Invention, that third phase of play.

But all is not lovely.

The Dark Side, list C

I compare my own work with that of others.

I tend to judge what others do as better than what I do.

I really can’t do this very well.

I’m jealous. “I wish I could do that.”

I feel I am being judged.

Now everybody can see my lack of cleverness.

I want to hide.

- Negative judgments like these were always present, but usually hidden.

- Heightening sensitivity to anything negative; a fragility. “I am really bad at…. “ “I don’t want to…” “This is not for me.”

- Playing requires existence at edge of our competence.

- We are doing unpredictable things on impulse, which leaves us vulnerable. We may tend to hold back a bit, take fewer risks to lessen exposure. “I’ll just watch.”

- We can feel pressure to do well. We know people are watching us. I want to look good.

- Putdowns hurt.

- Hurts when others don’t respond to us, which can quickly lead to passivity or even withdrawal. “Others don’t seem to like my ideas.”

- Materials are hoarded, grabbed, and coveted. We will fight for what we need if it is important to carry out one’s intention.

- Destruction of one’s work by another person is really bad.

- We need time to reach the result. “I don’t like being stopped early, before I’m finished, when I’m really getting into it”.

How does this fit with your experience?

Conclusions: seeing A, B, and C together

- Play comes alive through the positive social forces. Synergy fuels the fire and gives play the energy that sustains action through difficulties.

- Play is fragile. Any number of things can dump water on it, and the heat diminishes.

- Play can fall apart at any time, during phase two or even right at phase one, and never reach phase three. Seedlings are vulnerable to disturbance and can have a high mortality rate.

- Play consists of being spontaneous, present, and doing new things. Repeating old ways, doing what I did before, isn’t play: it lacks joy.

- Play may be delicate at first, but under the right conditions it resonates with a strong, determined dynamism, synergy, and creativity, like true leaves bringing energy for growth. Play may be the best that humans can be.

Anything to add?

Application

Our construction of Play has three components: (A) emergence, (B) the positive forces, and (C) the dark side.

At this point in the process this remains an adult-constructed view; it was built from several minutes of play with other adults in a college classroom. This could be, of course, a limited perspective, an inside-the-player view, that may not apply when one was on the outside of the play observing children.

That is a step, an essential step, on the way to understanding the Stewardship of Play, as this page is titled. Stewardship necessitates an outside-the-player view. Life happens; children do their childhood; sometimes they are engaged in play and sometimes not. Our construction of the concept of play has utility only if we can use it as we watch children and reflect on our ability to care for it.

A way to address the validity of these ideas is to see if it applies to children. We can watch a six-minute video recording. Two adults and four children are present. Three boys. One girl. The materials are long tube carpet roll cores, large coffee cans, yellow tennis balls, and a low sawhorse.

(BTW This was in the North Seattle Laboratory Preschool where I did all my taping and investigation. The adult child ratio was abnormal because this was a class. One of the ideas we were investigating at this time was whether a choice board helped or not. The children could voluntarily move their own clothespin to the symbol of the area they were choosing to play in. We decided this declaration routine made no difference at all.)

I invite you to watch for yourself. The idea is to see if you can see (A) the general sequence, (B) the presence or absence of positive social forces, and (C) indicators of the presence of the dark side.

If you watch this with other people, do these three parts apply here?

Before you read the next paragraph

Did you see emergence? the positive forces? the negative forces ?

Validation

The same 500 or so people agreed that their proposed, socially-constructed description of the concept of play-as-viewed-from-the-outside indeed has the sequence, became energized by the social world, and was subject to dark forces, such as the girl leaving unengaged, having possession of tennis balls. and walking through the center of other’s play. That agreement becomes a reality to them. It has form and affects what those people will do in the future. That is real to them.

Those who have (1) differentiated the emergence stages of play, (2) experienced themselves the positive forces and dark forces, and (3) found evidence of them in observing children’s play have achieved a milestone in pedagogy. Every participant should receive a certificate for their portfolio.

Your thoughts? What has changed for these people?

On to the next level: we address the conditions in the environment that help or hinder the spark and sustainability of play.

Metaphor of the Gardener

Before proceeding it is worth considering agriculture as a metaphor. Most plants grow naturally in their environmental niche. Some plants are grown intentionally in a niche provided by human beings. In either case, the genetic makeup of the seed contains the information needed to flourish that the farmer, gardener, or nursery worker desires to foster in its full expression.

The gardener views the plant from the outside and knows what to provide at each stage of growth: germination, seedling, and true leaves. The gardener does not encourage the seed to germinate, grow roots, or sprout leaves. The gardener works on the outside by attending to the conditions for growth to optimize the chances that the inside genetics come into fruition. The gardener fosters that full expression by ensuring positive forces are optimized and toxins are absent.

Educators, like gardeners, are engaged in environmental management—stewardship—assuming the responsibilities for planning and resources to safeguard the needs of others in an ethic of care. What we have done to define the concept has its purpose in shepherding and safeguarding the conditions that foster play.

Conditions for Emergence

The children are the players; we are trusted to conduct, supervise, and responsibly manage opportunities for children’s play, so it more than sustains, it flourishes. Stewards of Play have two jobs: (1) to select or provide a healthy environment, the “before the children come” side; (2) to keep things sympathetic and the dark forces at bay, the “during the children’s engagement” side.

I can recall my most treasured play experiences as a child, and I have student’s do this, too. The provocation I use is reading them Roxaboxen, a book that Bev Bos introduced me to, and inviting them share their best childhood play memories.

I can recall my most treasured play experiences as a child, and I have student’s do this, too. The provocation I use is reading them Roxaboxen, a book that Bev Bos introduced me to, and inviting them share their best childhood play memories.

Marian called it Roxaboxen. There across the road, it looked like any rocky hill—nothing but sand and rocks, and some old wooden boxes. But it was a special place. And all children needed to go there was a long stick and a soaring imagination.

List what those settings provided that enabled that play to be so memorable.

Picture Books for Kids Roxaboxen YouTube

What are the environmental components that enhance the emergence and continuation of play?

Compilation of Conditions

Consistently and uniformly, each class creates the same set.

- long stretches of time,

- friends with different abilities and experiences,

- no cleanup at the end, instead, the play space continues day after day, with various additions,

- found materials, usually natural, few if any toys,

- no adults.

How does that fit with your experience?

With that start, the participants began a lengthy discussion of those environmental components. One comment often occurred: participants need emotional safety, the idea that people need to feel comfortable to play or empowered to play. It’s an important problem, but it can’t be included on the list, because the players aren’t the subject of this discussion. We are erasing them as in the image above. We are trying to describe the before/during environment in which play flourishes.

We’ve erased the players, so where does emotional safety come from?

Below is a composite of lists created over many years. As you can see, at this point the lingering question of emotional safety has not been adequately addressed. I kept Emotional Safety on the board as we explored further. The physical safety guides, the physical conditions, became clear. Oddly, time was often the last to be added.

Physical Conditions

Physical Safety: the environment is free from dangers

Space: sufficient space is available that is open and adaptable so it can be altered as play develops

Time: long enough periods of time each day, as well as opportunities to extend work across days

Materials: in quantity, offering hands on experience, made accessible and visible, in variety, open-ended to be used in many ways, and aesthetic

Physical Well-being: spaces are warm and lighted and furniture is of a comfortable size for children, who are well fed and rested

Care

- Offer freedom.

- Observe without impinging on what is happening, being present with little, if any, involvement, documenting by writing down what children say, taking photographs and video of significant developments to reshow at a group meeting time.

- Be pleasant and present; model positive energy; recognize events of cooperation and perseverance.

- Recognize initiative: narrate inventiveness, make intrinsically phrased remarks, such as tricky or clever.

How does this fit with your experience?

Emotional Safety: Missing?

To get the emotional safety more fully addressed, we shifted to a discussion of printed text. I provided a handout of Quotations From Bev Bos, Before the Basics, the textbook I used because it had so many provocative ideas.

To get the emotional safety more fully addressed, we shifted to a discussion of printed text. I provided a handout of Quotations From Bev Bos, Before the Basics, the textbook I used because it had so many provocative ideas.

Most people benefit, at this point, from taking the time to read each numbered quote and talk with others before moving onto the next. It provides context for what comes next.

Here is a page of quotations from Bev Bos for you to discuss in your groups. One person reads the quote aloud, and then the group talks about what comes to mind. When ready, you can do the same with the next.

1. This year we had much more rain than usual. Everyone, frankly, was very tired of it. In the middle of sharing one day, I said, “Come on! Let’s go out and enjoy the weather!” It was pouring. We ran on the bicycle trail, lifting our heads up and sticking out our tongues to catch the rain. We laughed; we touched each other’s wet arms and faces. We talked about the dark clouds, and then we ran back in. The joy, the sense of play and friendship as we talked was overwhelming. Months later, children would say, “Do you remember when we ran in the rain?” When we talk of the best things we have done, very often a child will say, “The best day was when we ran in the rain.”

2. Children were not born to sit still. When I visit schools and I don’t hear children asking questions, arguing, even interrupting, I suspect that there’s little learning going on.

3. Children were not born to stand in line. Since most adults I know don’t like to stand in line, we must understand if we think about it how awful standing in line is for young children—all that energy and curiosity simply brought to a halt. Of course, its not. Standing in line is simply an invitation to pinching, poking, shoving, stepping on toes. In the many years I’ve taught young children, I’ve rarely found it necessary to line them up for anything. We can sing songs, tell stories, have conversations in during the time wasted in lining up.

4. As adults, we must first remember that we are in charge of the settings in which are children develop and discover; we create and control those settings for better or for worse. Sometimes, unfortunately, it is for the worse. Why that should be is very mysterious. Our very desire to do the best for our children makes us nervous. Although we have all been children, we forget what being a child was like. We begin to see children as objects, forgetting that we need to communicate with them or mistrusting our ability to communicate with them. In so doing, we lead them into mistrusting their own sense of what is good for them.

5. There is yet another way in which our nervous concern for our children leads to less-than-effective learning. Learning is a human activity. It needs to be filled with laughter, sometimes with tears, with infinite, painstaking effort; but it must never be mechanical. Child-rearing and education are a serious business. That doesn’t mean the have to be grim businesses. Rather the contrary. We need to develop a sense of joy in working with young children exactly in proportion to our sense of how important their learning is to us.

I hoped time for an open-ended conversation would be relaxing and playful. Usually people welcomed the freedom to talk. We get talk with our friends!

I watched for about ten minutes so they had enough time to really get going. Then I walked up to each group in turn with a stern expression and my arms crossed. I stood there waiting for someone to be talking animatedly, and I interrupted them mid-sentence. I asked rather formally, “Are you on #5 yet?” Without waiting for an answer, I walked off. Around the classroom I went doing the same to each group. Then I stopped everyone.

“I just did something to each of your groups. Would you talk now about what went through your mind when I said, ‘Are you on #5 yet?'” I heard outrage from some, a wave of guilt from being a bad student in others, and almost unanimous discomfort.

Why did that have such an effect? All I did was ask a teacherly question.

The answer gradually emerged as we talked about that experience. I changed expectations about what they thought they were doing. They were set up, right from the first activity of this course, with an expectation that when I created opportunities for small groups to talk together, they had freedom to do and say whatever they wanted. In a sense, they were playing as we defined it above. They could germinate, become seedlings, and grow their leaves of understanding. I had always offered freedom to talk about whatever they wanted, listened without interfering, was pleasant, and tried to convey that I valued their initiative. As a result, positive social forces were at work talking about these ideas and how true they were in their experience. Energy was going gangbusters!

Abruptly I changed the rules. They were suddenly not free to follow their flow. They were forced, by my power and privilege, to change their behavior to conform to different expectations. It was like turning off the lights: The Dark Side arose into the room.

Do you have any idea how often this happens to children when they start to be playful? Or why children play better when no adults are around? Adults, in an attempt to be responsible, interject a bit of guidance or share an imaginary worst-case-scenario—Be careful. It’s not OK to put sand on the slide. Watch out Diana is coming down.—immediately dousing the fires of spontaneity and removing their freedom to play.

This led to Care point #5:

5. Maintain clear, consistent boundaries and expectations, established beforehand. If new problems arise that modify those expectations, honor the children’s input and negotiate new boundaries and agreements in an immediate community meeting or later at a scheduled group time.

That’s a big idea. What do you think?

Emotional Safety: Is there more?

There was still one more missing piece of emotional safety to address. I asked participants to look into their life experiences. I asked them to list one or two things they do really well, difficult things that took time to learn.

What are some of the abilities you have that others recognize and value? The remarkable abilities that have become part of you>

Once those were jotted down, I asked them to pick one and write for a minute. What was it like in the very beginning when you were trying to learn to do that? They shared their experience with each other—a required opportunity brag.

What is self-confidence? What does it mean?

After several minutes, I called the groups together and asked them to define self-confidence. The discussion varied each time, of course, but usually we arrived at the same place. We had on the board something like the dictionary definition of self-confidence: (1.) Our self-assurance in trusting our abilities, capacities and judgements; (2.) The belief that we can meet the demands of an upcoming task.

Then it was time for the final prompt.

Where does self-confidence come from?

How does one become self-confident in some endeavor or in some challenging situation?

This discussion lead eventually to the conclusion—based upon people’s own experience in areas where they had built their own self confidence—that self-confidence comes from making mistakes and correcting them. The more mistakes you make and correct, the more confident you become. I am confident in my ability to bake bread, because I have made every possible mistake, including forgetting about it rising in the oven and later finding a swollen mess of spongy dough completely filling it. That never happened again, of course.

This led to Care point #6:

6. Trust children to fix their own mistakes.

Either alone or with the help of others, children can find new solutions, rectify their problems, or repair a wrong. When they get to create the solution by themselves, without adult interference, they develop confidence in themselves, confidence in others, and confidence in the power of belonging to a community.

With #5 and #6 we address emotional safety, not in terms of how children feel (not predictable) but in terms of two guides for own intentions as leaders. We can ensure in our play environments we are purposeful in two ways: establish consistent expectations and value the self-correction of mistakes.

At this point you can see the whole. What comes to mind?

Guides for the Stewardship of Play

We constructed then a shared concept of play and the two-part conditions of emergence (environs and caveats). We were now agreed upon guides for a Stewardship of Play for all the participants in this experience—a socially-constructed shared reality—this group could use to understand program planning for young children. The guides had a firm reality to everyone who participated in the process.

Construction of Play + Conditions of Emergence = Stewardship of Play

PDF file to reprint, use, adapt Stewardship of Play

Application

A week later we opened a discussion of people’s experiences with children after the participants built this understanding.

First they needed time for everyone to talk and be listened to. Usually fifteen minutes was sufficient for small groups of 3 or 4. Then we held a large group open discussion.

Participants consistently reported how they had changed. They became proactive in setting an environment that more directly enabled the emergence of Play. They made sure the materials they offered met the criteria they developed. They allowed more time, letting play periods go on longer. They found ways to safeguard important items so they could continue from one day to the next. They hung back and watched and saw that the children found their own solutions to their problems. They told stories of young children playing better together. They agreed that all this came about from applying their constructed agreements about Play.

Understanding Requires Activity

This is why we began with addressing how we learn an abstract concept. After all this work together, as a learning group, not alone, the suitcase with the handle “PLAY” contains a common understanding. No blah-blah lecture could ever transfer this abstraction into their brain. Knowledge (repeating back something) became understanding (brain interconnections). When they applied that understanding in their next week with children—the emergence, the positive and negative forces, and the physical and emotional guides—they all became Stewards of Children’s Play.

They also agreed what a pleasure it was to work with other teachers who had done this work, too. They naturally acted in concert, in the same ways, with confidence and a tangible sense of joy.

Teacher Tom

I invite you to read a great deal of Tom Hobson’s thoughtful writing about play, education, and human communities. He is an exemplar of a Steward of Play.

Why Children Bicker as They Play

That’s what physical safety and emotional safety looks like. That is what care looks like. It’s not “encouragement.”

Time: 15′ + 15′ to begin Play. No toys. Consistent expectations called “Agreements.” Trusting children to fix their own mistakes.

Play like this is how children become good people.

Transformation

When 10% of the world’s population has lived community Play, created by design for children ages 2 to 6, the next epoch in human evolution begins, marked by the date humans intentionally ensure the young become stewards for life on Earth.

In Memoriam

To bev bos and all Stewards of Childhood

College Teaching

It has been a long slow learning curve for me—17 years of teaching young children—before I began to understand enough to teach a course for others. I was familiar with the normal slew of ECE textbooks, I was leading a preschool, and I was teaching advanced students, but I never thought I understood something as basic as preschool program planning, the first course for incoming students.

Program Planning

Like all the other courses I taught, I wanted to ensure that this new one was constructivist, that is, we—myself and the participants in the class—would build our understanding. Working with young children is less about something to read or know: what matters is how one acts with children. We are looking for truth and beauty in being.

I have never used a general text, because I never learned much from any I ever read. I never liked listening to lectures either, which is how I was treated in my education. That was out, too. I rather liked finding engaging, rather unorthodox things that provoked lively discussions. I especially liked the brazen joy of Bev Bos, whom I loved. I assigned one of her books to give everyone a healthy aesthetic and spent two months designing ways for students to assume the responsibility for developing, in concert with their classmates, how our understandings about schools for young children grow within us.

Designing a College Course

Every course I have taught I designed from scratch, to not “impart” knowledge, but to enable people to actually become better with children. If you’ll bear with me, I’ll briefly highlight I how learned to do that…

First, I defined the ultimate goals—what people are able to do in their futures down the road somewhere in their lives. Then for each goal I chose the visible performance that could happen in this term that would prove a participant had the the capability to continue to pursue those goals. The list of those performances became the requirements for the course. When I could see them on a page, I chose a verb from Bloom’s Taxonomy, from low to high, to convey that course objective, depending upon how much time could be devoted to it. Anything up into the analysis or synthesis level meant a lot of class time was needed. These objectives became the performance requirements for the course, exactly what people had to do that earned their grade. I used an 80 point system where grades were computed by adding the number of points earned, subtracting 40 and dividing by 10. The description of all of that was the syllabus. To figure out my part, the course sessions, I listed the major concepts, the deep ideas that the course endeavored to convey, and placed them in a logical order, basic to advanced. These sequenced the content over the term. The most basic concept became the content of the first class. That first session must always start with the life experiences of the participants, building from what they know and have done.

This logic led me to understand that the first topic, the first session of CCE 125 Program Planning, had to develop a shared concept of play as you see above.