Arithmetic Skills

A vision of five-ness? What does that mean? We have to be clear what we are talking about. Abilities in arithmetic, in these early years, can be classified as skills (practiced abilities), concepts (mental understandings that are constructed over time), and making connections to symbols once those understandings are strong. A vision of five-ness is a concept, not a skill. Counting these beans is a skill.

When my son, Benj, was 4 1/2 years old I was in my second year of teaching math for young children. In putting a class together I quickly discovered the literature on arithmetic and the students in my class had no common vocabulary. There was no consistency in the names for the basic arithmetic abilities. For example, it was rare to find two people using the same word for what actually constituted counting. The same was true of presenters at national math education conferences. What a mess.

When my son, Benj, was 4 1/2 years old I was in my second year of teaching math for young children. In putting a class together I quickly discovered the literature on arithmetic and the students in my class had no common vocabulary. There was no consistency in the names for the basic arithmetic abilities. For example, it was rare to find two people using the same word for what actually constituted counting. The same was true of presenters at national math education conferences. What a mess.

To solve the problem I did what I usually do, I had the students work together to define the skills and concepts. To get this to work I recorded my son, Benj, who happened to be in the middle of the 3-6 age range I am addressing here. I was amazed about how much complexity could be found in that unedited videotape! Benj and I were really lucky that day.

I recorded the essential abilities, which I presented as tasks for Benj to do. I did not put names to those abilities, so we could watch together both the abilities and the difficulties a child faces in early arithmetic.

I would show an ability one at at time and pause for the students to discuss what was happening.

That tape is coming up next. If you have the chance to do it this way in a discussion with others, I highly recommend taking the time to do the same way, pausing the video. You’ll see how people’s perspectives are widely different, because teachers, math materials, and textbooks often fail to distinguish these tasks. Sources use different words for something as simple as finding out how many lima beans are in that first picture. Can you do it?

What would you call the ability to say, “Fifteen”?

Five Reasons for Watching This Video

- If you know each ability, you can see when children do it, as well as precisely model skills.

- Seeing the distinction between concepts and skills helps people trust the natural processes of the child’s brain and recognize how children have to figure out numbers themselves.

- You can articulate to parents and supervisors what’s important.

- You can better evaluate mathematics materials, video games, and toys.

- Formal assessment asserts power. Assessment puts a child at risk of failing, which they have to do in order to find an upper limit. It is a lesson in being stupid, so it can hurt.

- You can clearly distinguish assessment from education, which people often assume are the same.

The video demonstrates assessment not teaching. Budding educators and novice parents often confuse making a child count stuff as helping them learn. Benj is not learning these skills at the time he is being recorded: he learns in real life. Assessment is totally unlike education, which is the provision of opportunities for encountering provocative things in a community of care. Education is the sun, soil, and water for carrot seeds to do their thing over weeks and months. Assessment is more like plucking a carrot out of the ground and eating it.

To have this experience be most powerful, I think, is to be diligent and not look at the list of skills and concepts below the video. I recommend watching with others and stopping the video piece pausing to discuss what each ability is called.

I find it most intriguing to try to figure out what Benj knows and is able to do, which when you hear other points of view, you can see more of what is happening. I can see the anxiety here: being on the spot, exposed, videotaped, and trying to do the very best.

Afterward, you will see that I missed having him count on and write numerals.

Arithmetic Skills and Knowledge

Download PDF Arithmetic Skills

Envisioning

The names for the skills, symbols, and concepts I use are the clearest ones I know. One name you won’t find elsewhere is Envisioning — my name for the ability to imagine the missing quantity, in every combination, for a given set. Others have called this “really understanding” a number. The term I see most used is partitioning, but that word falls short: dividing, or walling-off, fails to highlight the conceptual root.

Envisioning a quantity recognizes that somehow a set is represented in the child’s brain as both items and holes. The imagined beans under the cup are the “holes.” To have those pictured in one’s mind is a lasting construction, never to be forgotten. No one gives concepts to a child: they have to construct it in their neurology. Envisioning is the ability to imagine the amount withdrawn—the unseen—while experiencing the perceptual dominance of the remainder, the two big beans, right there in view. The child must have some kind of representation in their mind of the whole set. You see five; now you see only two, and those two beans dominate your thinking.

Envisioning a quantity recognizes that somehow a set is represented in the child’s brain as both items and holes. The imagined beans under the cup are the “holes.” To have those pictured in one’s mind is a lasting construction, never to be forgotten. No one gives concepts to a child: they have to construct it in their neurology. Envisioning is the ability to imagine the amount withdrawn—the unseen—while experiencing the perceptual dominance of the remainder, the two big beans, right there in view. The child must have some kind of representation in their mind of the whole set. You see five; now you see only two, and those two beans dominate your thinking.

I think we all may have experienced a very young child, who is given a cookie, raising the other hand for a second one. Envisioning two. Inside the brain, somehow.

I think we all may have experienced a very young child, who is given a cookie, raising the other hand for a second one. Envisioning two. Inside the brain, somehow.

I think envisioning the remainder of a set given a subset is the BIG ONE, in all the combinations for that set.

It is fascinating how the quantity represented in the mind corresponds to the age of the child. It’s remarkable: the set generally increases by one: one increment per year.

I have found I can say with confidence that a child is doing well at arithmetic if they can envision the number of their age before their next birthday. If a child can envision 3 during the year they are three years old, envision 4 during the year they are four, and envision 5 during the year they are five, I have every confidence that they will envision 6 by common school age, where envisioning to 10, the underpinnings of addition and subtraction, are tools being employed.

I have found no reason to worry about the close stragglers: envisioning one’s age minus one—that is, a four-year-old can envision 3 but not 4—I have found them doing fine. Like every other ability, some children really soar in singing or dancing or striking a ball; some really soar in arithmetic. Even though we might want our child to excel everything, not everyone has to soar.

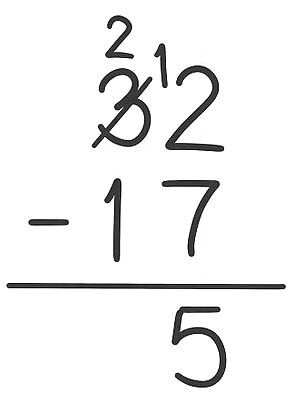

Envisioning provides insight into a young child’s arithmetic competence. Because performance in manipulating symbols depends upon understanding the concepts, not counting skills nor following any algorithm the children will be taught later, such this one. If you have to follow a procedure without understanding the beans and holes, one might end up saying, “I’m no good at math.”

Envisioning uncovers the fundamentals pervading most aspects of arithmetic and computation the child encounters later. (You might note that this item is missing from kindergarten readiness tests. You can look if you want.)

Envisioning uncovers the fundamentals pervading most aspects of arithmetic and computation the child encounters later. (You might note that this item is missing from kindergarten readiness tests. You can look if you want.)

I like it when I discover something simple like this; I also like creating opportunities where this understanding is constructed.

Research shows this is true. Related research from the University of Missouri.

A Focus on Numerical Age

I know it sounds simple, but I had never thought that the opportunities children most needed matched their chronological age. Five is the center for five-year-olds; two is the center for two-year-olds. Age is a rough guide for activities in arithmetic when thinking of mathematics and design in a horizontal curriculum, not a vertical one. A vertical curriculum implies that faster and higher are better than wide-ranging intellectual experiences focused on deeper understanding. It seems to me that best thing one can do for groups of children is to offer a broad spectrum of opportunities and games using the children’s age minus 1 and slowly creep them upwards to age plus 1. A reasonable expectation would be that when children approach the age of six, they are close to envisioning five. With a solid image of five-ness as items and holes, six-year-olds will easily get six.

When I learned this, all the pressure to push disappeared. It’s comforting to know that children have at least four years play and following their natural interests: from the time they know about two crackers to the time they discover the magic of six is a very long time. Six, by the way, is actually very interesting.

Six

It seems the children who envision six, seem to quickly expand that five-plus-one to five-plus-two, since they already have mastered all the combinations of five. So, children seem to get seven, eight, and nine close to the same time. Adding increments of one onto a deeply understood five is the basic of arithmetic and opens symbolic manipulation with our number system. Numerals then represent deep concepts, eliminating the biggest problem children have later.

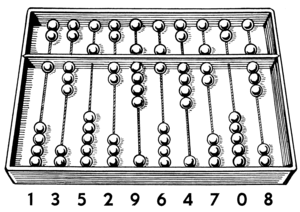

You can see five-plus displayed in the beads on this abacus image. The upper beads represent five, the lower beads represent one. Quantities are represented by sliding the ones up or fives down to touch the center bar.

The centrality of five plus one is visually displayed on the abacus, but it can more easily be represented with the fingers and thumb of one hand, like below. The quantities 0 to 9 are visible on one hand, not two, by using the thumb to represent five. If we commonly used one hand for 0 to 9 this way, that is society decided to standardize number this way, not as in American Sign Language, possibly envisioning might be enhanced. [You can find videos on YouTube showing how much calculation can happen on two hands, the left hand representing tens and the right hand representing ones.]

Symbols, the numerals, remain difficult for children to use if they have not constructed the concept first. Envisioning gives us a clue.

Subitizing

Subitizing is another way to see the importance of six. Quantities of six and below can be immediately grasped without counting them out. Above six and it gets tough. You can check this for yourself by looking at the dining chairs and the mirrors. Instead of subtilizing (grasping the set as a whole), people begin to subdivide the larger set of chairs into smaller sets and put them together in their head. Some people can grasp the six-ness of the mirrors; others group subdivisions. Here is the edge of subtilizing. Six, again.

Subitizing is another way to see the importance of six. Quantities of six and below can be immediately grasped without counting them out. Above six and it gets tough. You can check this for yourself by looking at the dining chairs and the mirrors. Instead of subtilizing (grasping the set as a whole), people begin to subdivide the larger set of chairs into smaller sets and put them together in their head. Some people can grasp the six-ness of the mirrors; others group subdivisions. Here is the edge of subtilizing. Six, again.

The amazing shift at six must be a brain thing, most likely evolving in concert with our hands. We have five fingers on each hand, so two hands can represent quantities to ten. I wonder if the centrality of age with deep understanding of number is related to the fact that common school begins in most countries when children have reached the age where they can hold two things in their minds at once, like six. With that foundation, symbols easily become thinkable. That’s why envisioning is essential to the rest of arithmetic.

And why all those worksheets for preschoolers should be recycled into something useful.

Assessment

Although I personally resist external demands to test children, I am a big fan of assessment for my own learning. I find it a necessary step in professional development to at least partially grasp how the emergence of skills and understandings proceeds. After a systematic look for a year or two, I trust an educator to never formally assess again. He or she can simply observe. That’s being a professional. I think an essential part of early childhood educator’s preparation is to systematically check out all children on the asterisked items on the Arithmetic Skills and Knowledge document at least twice a year for two years. This study enables one to see the missing — one’s own envisioning of learning — and to see how differently skills and concepts emerge over time. People taking my course in this were required to do this at least once.

Understandings Discovered

Here is a sample of what participants discovered in checking on arithmetic skills and concepts with young children in their classrooms and child care spaces.

- We must always keep it fun.

- We can stop any time we need to; we can always come back later.

- Even if we have a class of children all the same age, they are at vastly different levels; that is the way it is.

- Assessment checks can show us what level to do our demonstrations and offer opportunities so that those who are at the “lower end” are entirely successful and feel smart. The “upper end” is always just fine.

- Often we are surprised by what is going on that we did not see before.

- When children are wrong or can’t do a task, we must remain authentic, present, and truthful.

- We focus on what we can see that is successful, for that is the only thing we know; when a child is not successful, we know nothing.

- We maintain the clear distinction between feedback (right/wrong, yes/no) which people need and judgment (good, bad) which they don’t need.