How We Talk About Reality

B: It’s hard to get sand out of hair.

C: That’s not safe.

We have a responsibility to reflect upon the ways we talk about what is happening.

The way we describe what others do depends upon our willingness and ability to notice and upon the ways we use language to portray it. If we want to be effective, we have to address both issues.

The way we describe what others do depends upon our willingness and ability to notice and upon the ways we use language to portray it. If we want to be effective, we have to address both issues.

In all fields of study, every discipline or trade, becoming skillful and effective requires precision in communication. Each term has a specific, agreed-upon meaning. Communication between people has clear procedures and required content. Learning the language and using it intentionally is essential to being effective in the work.

Common ways of talking hinder effectiveness in teaching and learning, too. What we think about children can be insightful, for sure, but it can also limit the kinds of things we are noticing, and, more essentially, spark an emotional reaction causing unnecessary barriers to rise. This is especially true when we are addressing sensitive issues such as behavioral difficulties. All of the Protocol work in this section on managing behavior depends upon establishing clarity in language as we construct a strategy to help a child in distress.

Theories of Action

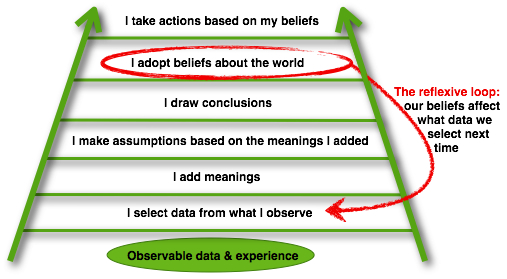

The ladder of inference described by Chris Argyris begins at the bottom in the green oval. Each rung upward shows how one’s theories and beliefs become increasingly distant from the events themselves and then become fixed and resistant to contrary evidence.

The ladder of inference described by Chris Argyris begins at the bottom in the green oval. Each rung upward shows how one’s theories and beliefs become increasingly distant from the events themselves and then become fixed and resistant to contrary evidence.

If we fail to study how we discuss reality, we may find ourselves continuing obviously ineffective actions. If someone asks us kindly why we do things this way, we might respond by eagerly expressing our beliefs and opinions, even though when we act, we often don’t act the way we believe. The result is what we all have experienced time and time again: we blame the child or parent, we avoid looking at contrary evidence to our judgments, we become resistant or defensive when there is disagreement, and—in spite of the fact that we are half of the problem—we rarely volunteer to change. Chris Argyris says this is simply the way things work.

To be effective in helping others be the best they can be, we attend to how we talk about reality. We become wiser, more consistent, and more effective when we refer to what is actually happening, the observable data and direct experiences we have had. Once we agree upon the facts, we address the meanings of those facts. Having agreement on how we talk, therefore, becomes basic to everything. We can’t relax into assuming that my beliefs or your beliefs are a reliable base for action. We examinee facts in order to build communication precision.

Three Levels of Inference

When we are careful to ground our theories and experience in what actually happens, we avoid the danger of that reflexive loop. The three levels of inference are three kinds of realities: factual reality, an agreed reality, and one’s own reality.

Physical Reality — What is directly observable to our senses, what we can see, hear, taste, touch, etc., is experienced as a fact. In relation to children, physical reality is observed actions — what a child does or says — and data we have about it. Child pours sand on another child’s head. Child causes another child to cry an average of 2.5 times a week.

Socially-constructed Reality — After a small group of people discuss the different ways we consider those physical realities, they might conclude that the event under discussion has at least a few certainties that group can agree upon. The creation of these agreed, or at least acceptable, conclusions take on a kind of reality, because they are conclusions or shared ways of thinking for those who participated in that discussion that one time.

Others who did not participate in the agreement may differ, but this one group does agree, at least for the moment. For example the group may all agree that It’s hard to remove sand in your hair. When a co-constructed meaning is established, it becomes normative for that particular group. It has an operational reality; that group of people who agreed can interpret events with shared expectations. Socially constructed agreements build a team view and enhanced communication, with the expectation that these agreements can easily be changed or modified at any time.

Personal Reality — Fortunately, we all have our own judgments, opinions, and beliefs acquired from our life experience. Most people are more than willing to share them, almost automatically, without necessarily having to ponder very much. I think it’s not safe. Opinions contain both richness and rigidity, but who really knows if one opinion is more valid than another? The problem is how to move forward toward mutual action when all that happens is the sharing of opinions.

In a nutshell, the three levels of inference work like this: a particular set of people might agree with the previous paragraph. If they all nodded affirmatively to accept that in order to work together most effectively, we are willing to operate under the mutual assumption that opinions and judgments are unreliable. That agreement is no longer a personal reality but a shared reality, because it guides how the group works. Each member of the group accepts the responsibility to act in accord with that agreement, until the team decides to modify it, based upon events in the physical reality they encounter.

Opportunity to Distinguish the Three Levels

I refer you now to the 05:23 video of Cory at The Easel on Vimeo. This is my way of offering the opportunity for people to construct their own understanding of the distinctions among the three kinds of statements about reality. When we educate others, we never really know what goes in their minds. We read the clues we have and figure out what those clues mean.

Cory is painting several pictures in row. In the video we can find subtle clues to what he is doing, so watching him on videotape gives us a unique opportunity to practice distinguishing the three levels together with all of us looking at the same data.

We have the physical reality of what we see and hear in the recording. We have our own thoughts and opinions about it, but can we agree upon what his is trying to do? What can we say his intentions are?

I invite you to take the plunge. After all, those words above are simply words until one applies them to real events.

I offer a PDF exercise sheet with boxes to record ideas. It’s best when groups fill these in together after watching once to see the flow, talk about first thoughts, and watch a second time with those thoughts in mind. Once you have experienced the problems of co-constructing agreement, I link a PDF key as an example of how a group might fill in the boxes.

A door to Action Opens

The Behavior Management Protocol keeps returning the conversation to the Physical Reality as we discuss what to do. We build from facts. When we have agreement on what those facts mean (as far as we know), we establish a new base for further action. Instead of dreaming about an adventure, we are moving forward.

The agreements we have become actionable; we can take a coordinated step. That opportunity opens only when we have arrived at a Socially-constructed Reality. accepting for now that we can always change it. We recognize our varied Personal Realities, but they don’t step us forward together.

Changing What We Do Takes Time and Diligence

Children are learning; we are learning. The learning and changing can be beneficial in enhancing opportunities or it can be destructive in hardening habits that lessen opportunities. Regardless, learning is always present; people change. Whether it is enhancing or binding depends upon the experiences we have in the moment. Some children learn to behave in undesirable ways that can become entrenched. When adults bring their own entrenched ways to the encounter, too, we’re stuck. Both the managers and the child have to find a path that enhances their lives.

Children are learning; we are learning. The learning and changing can be beneficial in enhancing opportunities or it can be destructive in hardening habits that lessen opportunities. Regardless, learning is always present; people change. Whether it is enhancing or binding depends upon the experiences we have in the moment. Some children learn to behave in undesirable ways that can become entrenched. When adults bring their own entrenched ways to the encounter, too, we’re stuck. Both the managers and the child have to find a path that enhances their lives.

A convention for coordinated action

The management protocol that this section steps you through creates the opportunity for a community to reflect and explore ways to correct and restore well-being and wholeness. It is not the only path, of course. Many paths can lead to movement out of locked habits towards personal presentness and congruity. I present a protocol because this organized approach has been well tested and changes behavior rapidly.

- It works (1) because it relies upon clarity of the physical reality of this one unique situation and (2) because this one unique group of people, who know and live with that child, co-construct what to do.

- When the managers have input to creating the choices, they become confident in them.

- If one has a voice in the decision on the choice of action plan, one has buy-in to act in accord with the others.

- If the first plan doesn’t change what is happening in a satisfying direction in a week or so, the group changes the plan. The managers act with consistency to see if this specific approach actually works and, if not, change it quickly.

Since there is so much material to cover, each step has its own page. You can download the Behavior Management Protocol Form now as a navigation guide and mental organizer or download it at the end after sampling each piece of the pie.

Since there is so much material to cover, each step has its own page. You can download the Behavior Management Protocol Form now as a navigation guide and mental organizer or download it at the end after sampling each piece of the pie.