Listening Actively to Deep Emotions

The goal is to hear the child’s world without judgment while communicating full acceptance. To that end I offer a convention, ordered intentions, to optimize the chances for actually helping. For me, some opportunities work better than others, but I know I have a practical strategy that optimizes my leadership.

Active Listening Convention

Imagine you have a child who is upset, fearful, withdrawn, hurt, etc. These are steps in using this opportunity for mutual benefit.

- Describe what you physically see.

- Paraphrase whatever message the child is sending. Keep continuing to paraphrase. Share something parallel in your own life. The goal is to deeply hear without judgment.

- Offer names for the emotion(s), avoiding the words mad, sad, and angry. Here is the link a reference sheet: Vocabulary of Emotions PDF .

- Describe the current situation and the opportunity options available at this moment.

Applying the Convention to Grace

1. Describe what you physically see.

State the facts without using emotion words.

Examples of physical facts:

You’re out here by yourself.

You’re in the hall.

Here you are by the cubbies.

Avoid

What’s going on Grace?

Why are you out here?

You seem upset.

Why start this way, without asking questions or assuming you know what is going on?

Stating the facts as you see them, what you hear or see, allows the child to initiate to you rather than respond to you. Questions require responses. Initiations are usually more complex than responses, so it may be worth waiting to see if they emerge. Maybe she doesn’t want to explain it to you or can’t find the words to explain the complexity of what she feels happening right now. So the first thing that happens to her after Taryn’s affront is to have to explain it to you? That seems rather insensitive, doesn’t it? Besides, when people are living their upset-ness, they usually aren’t deft with words. The observation statement of just the facts of what you see and hear sends two important messages: (1) I am now available and (2) I care. If she wants to talk, she has an opportunity.

The intent of step one is to spark an initiation from the child to begin a conversation. If the child does not initiate, the most effective thing to do is sit down and be with her for a comfortable amount of time, silently present and expectant of an initiation, without further prodding.

If you skip ahead and discuss emotions, you are assuming you know what Grace is feeling, which has a high probability of being off the mark. Then too, you might not learn the nuances of the situation. It’s generally a good practice to assume you don’t really have enough information at this point to accurately choose words that fit her experience. This is a crucial time to tread lightly.

2. Paraphrase whatever message the child is sending.

Restate their message in your own words without naming emotions.

Imagine Grace says, “I’m never going to play with Taryn again.”

Examples of paraphrases:

You’ve had it with her.

Done, huh?

That’s the last straw.

Avoid

You’re never going to play with her again, right?

Why?

I don’t think that is really true. You’re such good friends.

You’re angry at her.

The best paraphrases restate the underlying message exactly, in different words entirely, and are usually short. It’s how you might summarize the message in a brief way in your own words. A successful paraphrase indicates to the child that you understand what she means. If it is off, the child will usually correct you. A paraphrase connects and is the most likely avenue to further conversation. A child is more likely to expand on what she said than with any other kind of response.

Repeating the child’s words is not a paraphrase. I call it a parrot. If people did that to you, you might find it not only boring but also demeaning. A parrot doesn’t communicate that one is has caught the meaning.

Keep continuing to paraphrase as appropriate. If you want to draw the child out further you can share something exactly the same that happened to you in your own life. For another discussion of drawing out the expression and elaboration from others you can visit the Cultivating Conversation topic in the menu. One of the analysis tools one can use to examine conversations is Responsiveness. In developing that idea I offer The Responding Convention, another set of ordered intentions like this one with a set of practice activities linked from there.

The goal of the second step is to draw out as much as you can about how they see it, without adding any your own lessons or advice. Stay light to hear without judgment. Hopefully you can begin to piece together the emotions she is experiencing in this precious moment.

3. Offer names for the emotion(s), avoiding the words mad, sad, and angry. Use the linked Emotion Vocabulary chart as a reference. Chart: Vocabulary of Emotions PDF

Examples of nuanced vocabulary:

If that happened to me I would feel abandoned and disappointed.

I can imagine feeling crushed. (shunned, resentful, perplexed, or any appropriate word you can find on the vocabulary list)

Avoid

You’re mad.

That’s feeling devastated.

As the Vocabulary of Emotions web page notes, mad and angry lead to yelling or violence, sad leads to tears. Contrast those three with any on the list. What do you do when you are resentful? You think. You communicate. You write.

You have no right to tell another human being how he or she feels. You can offer words as a possible guess by talking about yourself, but not declare your opinion as fact.

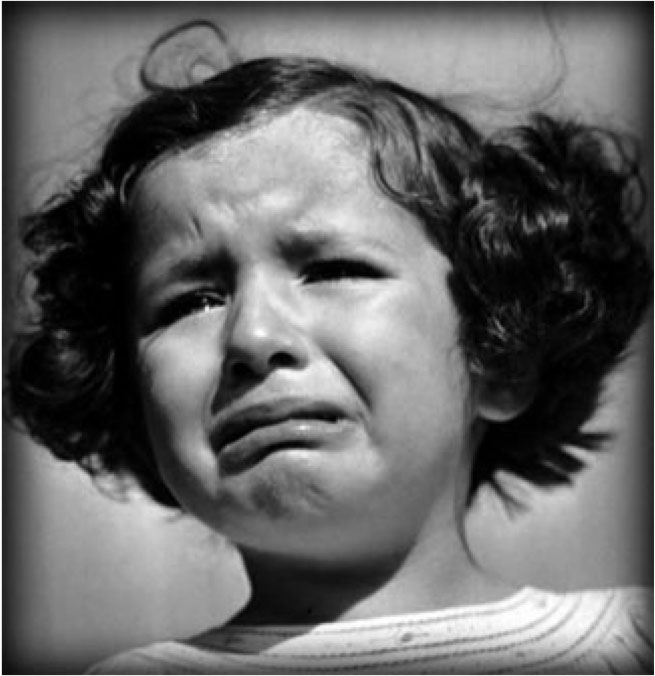

Using the emotion vocabulary at the time of the emotion is how one becomes emotionally intelligent, not from looking at a picture of an unknown child with a grimace on her face and answering a question such as how do you think she feels? The other effective way people learn emotion vocabulary is from stories that call up emotions and describe them.

4. Describe the current situation and opportunities available

Examples of offerings to get back in the groove:

Well, it looks like we have about fifteen more minutes before cleanup.

You probably have enough time to try something else.

I could sit with you back in the room, if you’d like.

I could use some help setting out the snack.

The Purpose of the Active Listening Convention

Emotional times are always challenging. Having a rough agenda in mind can help one say calm and present. The act of recalling the convention is a reminder to treat this as an opportunity to learn from children and to connect as fellow human beings. It’s not a problem to be solved, rather it is time to open ourselves to each other.

It helps if we intentionally minimize the power differentials that are naturally present, which we can do better if we pause and not react automatically. The easy mistake to make is to ask questions. What happened? How does that make you feel? Those wonderings come easily to mind.

The enhancing role seems to lie in attending to our own compassion and authenticity. The ability to use the chart to find a range of vocabulary and intensities supports the full spectrum of awareness for both you and the child. With practice these expressions become more nuanced and generative. Both parties are changed by the encounter. That’s the ideal, I think.

Examples of the Active Listening Convention

Juniper

Juniper pouts and cries when she has a problem.

When I approach at these times she usually screams at me.

Today I saw her in a tantrum over by the fence. I waited a few moments and then went over to her.

I said, “You have your arms crossed.”

Juniper: “Estelle won’t play with me. I asked her nicely, but she doesn’t want to play my game.”

I said, “She refused, huh?”

Juniper: “I even said ‘please’ two times.”

I said, “Wow. That happened to me before, too. I really felt abandoned. I didn’t like it at all.”

Juniper: “I didn’t like it either.”

I left her alone and in a few moments she was playing with another group of children.

Colin

Colin came into school with a scowl. He grabbed a block in each hand and spun around like a helicopter.

I said, “You are swinging blocks around.” Colin continued to spin.

I said, “I invite you to come to the art table and draw a picture if you wish.”

Colin drew a picture of a person on the ground with a sad face and a person in a plane waving and smiling.

I said, “I see two people in this picture.”

Colin said, “This is me and this is my daddy flying for his job.”

I said, “You wish he was here, don’t you? I do, too.”

Colin curled in my lap and started crying. I let him cry and held him.

I said, “It feels miserable, I bet.”

After a bit he brightened and he said, “I like going to the park with my dad and riding on his shoulders.”

I said, “That sounds like a lot of fun. You could draw that, too. I am going to draw a picture of what I liked to do with my dad.”

We compared pictures afterward. He laughed at the way I drew my dog.

Andrew

After arriving, Andrew washed his hands and began frantically looking for something. He was looking for his dad. He began crying.

I said, “You are running around with tears in your eyes.”

He said to me, “I wanted to say goodbye.”

I said, “You didn’t see your dad leave, huh?”

“I’d feel a bit disappointed.”

“Well. It is snack time next. We have a telephone, you know, we might try to call him.”

Summary Document PDF Leadership & Care