Core Item Portfolios

It’s time to take another look at the word “assessment.” Not all assessments of children’s learning are beneficial: some assessments are causing harm, others are distractions. With the exception of Learning Stories, almost all externally required assessments are lots of work and of little help. The word assessment has often rationalized external requirements to gather bits and bobs without proof that the results benefit our clients—the children, the families, and the school. If we wanted to do assessment that matters, we might first look what we mean by “assessment.”

Useful Assessment

The concept of assessment in education is pretty broad, but it generally covers all the ways we gather information to enhance learning. In the end, the purpose of assessment is to inform practice, but, as most of us have experienced it, most assessment discussions are about implementing externally imposed measures, without addressing how meaning is derived from that information nor how information is used for the benefit of the client and the community of the school. We could do useful assessment instead.

When we consider how to design useful assessments of learning (which means changing busy work to useful work),

- we first specify the important things for children to learn,

- we specify who cares about the results,

- we design a format that engages the audiences that care,

- we provide opportunity for those audiences to participate in drawing conclusions from the evidence,

- we create ways to record both the information and the conclusions over a period of time long enough to see growth in what we know and do, and

- we trust those who have close relationships with the children to figure out how to make beneficial changes in the life of the school.

Six components define how assessment informs practice. If we wanted to see an example that builds up from the children and families, I invite you to read further about building a Core Item Portfolio for every child in a school.

Becoming Who You Are

I offer you here a narrowly defined kind of record that I have experienced for twelve years. This system documents, in an engaging way, the progression of experiences in three evolving domains of accomplishments, events, and products in three areas. A physical book or binder compiles selected events as the child grows. It follows the child, year by year, from classroom to classroom, from first entry all the way to common school age. It includes blank forms for periodic reflections, completed twice a year, of the three parties who most care: the child, the family, and educators.

In my twelve years of experience, an excitement appears for families and children in the second year. The children, the families, and the educators experience a continually reviewable story of contributions, competencies, and dispositions that highlight their fully positive uniqueness. The Core Item Portfolio becomes a treasure to review throughout life.

A Core Item Portfolio, such as the one I suggest, IS NOT…

- not academic—it is intellectual;

- not linked to developmental stages—it celebrates uniqueness;

- not perpetuating racial/class biases—it opens opportunity for all perspectives;

- not measuring or judging—it offers the child and the family the opportunity to construct their own meaning over time.

Educative Assessment

Schools might be more ideal if they actually created spaces for children to grow according to their unique capabilities, always emerging at different rates, gradually over time, as determined by their genetics and their life experiences.

I think we can agree that those life experiences can be wholesome or detrimental. Schools may profess a wholesome intent, but we might agree that many schools are actually detrimental in practice: their traditional systems often create a coercive climate and insist upon mandated experiences that are clearly not beneficial for all children. In the continuing discussion of school reform, policy makers seem to ignore reality and the appeals of educators and continue meaningless testing. It’s supposed to make it better: reality proves it does not.

Emergence

One thing we know for sure: however much we demand and test, schools cannot make anyone learn. Interestingly, the same is true of farmers: no matter how much they demand or test, farmers cannot make crops grow.

I like to think about the provision of educational experiences and spaces using an agricultural metaphor. Farming or vegetable gardening seems to illuminate what is happening when we help others grow. We could imagine children as carrots and educators as farmers. Farmers don’t make carrots grow. They see seeds, then seedlings, and later lacy leaves, while the carrots, the abilities and dispositions educators deem essential, grow underground, naturally.

Farmers know that carrots need rich, teeming soil, moisture, warm energy from the sun, and no toxins. When conditions are proper, a carrot seed follows its genetic coding stuff to grow, over time, to be all it can possibly be. Like learning, carrots don’t grow in a day; we can’t even see them change.

Farmers know that carrots need rich, teeming soil, moisture, warm energy from the sun, and no toxins. When conditions are proper, a carrot seed follows its genetic coding stuff to grow, over time, to be all it can possibly be. Like learning, carrots don’t grow in a day; we can’t even see them change.

We could use this agricultural metaphor to look at the meaning of assessment. Farmer’s job is to grow carrots for market. To be successful selling carrots, they have to assess how carrots grow; they want a crop that is bountiful, flawless, tasty, and nutritious. When farmers encounter a problem in the growth of their product, they have direct responsibility to do something about it immediately. It goes without saying that the farmers are the only ones who can take action. Only they can see what to do and fix it: filing a report isn’t needed: direct action is.

Local Evolution of Conditions for Growth

Through constant attentiveness, farmers work to tweak growing conditions in a beneficial way, using the best information they have in order to apply their expertise. If they can do something right away, they will; if not, they will begin work on how to make the next crop more bountiful, flawless, tasty, and nutritious.

If we apply this idea to schools, educators would have the same kind of responsibility to tweak using the best information they have. Educators naturally care to alter both the immediate and long-term conditions for human beings to become more fully whole not only now but also through the rest of their lives.

Imposed Assessment Systems

Unfortunately, unlike the farmer (and unlike any other occupation, for that matter), the political forces that control the resources for commonly funded schools require educators to assess in ways that do not provide information needed to tweak their environments. Rather than trust them to do their own inquiry and correction (and provide the resources they need), federal school policy in the United States (and many other countries) requires costly, corporation-built assessment systems, which are coercively attached to the money the school needs to function. It’s mandated. No assessment? No school.

These imposed systems do not show they improve the lives of the children nor do they ensure all children do well; they simply are rules and imposed requirements. Since those behind such policies have no knowledge of the children nor how to educate, they want numbers, checkmarks, and scores—artifices: unrelated to the care of human beings. Back to the farmer, imagine the Department of Agriculture requiring farmers to fly drones over their carrot fields, to upload data to satellites, to create centralized reports no one reads. That would be crazy. Instead, policy logically lets farmers do what they know best: walk their fields, touch the soil, and examine their carrot plants.

Ethical Practices

Centrally imposed systems don’t love the children, talk to them, or listen to them. It may even be unethical to participate in policies that waste resources and cause harm to our clients, especially constraining them without a shred of evidence that requirements make anything better. Centralized systems impose extra work—dreaded, useless, and irrelevant. The clients lose, and the educators—the only ones who can alter the conditions for growth—are remain underpaid and distrusted.

I think most people would agree that providing administrators and educators with the resources they need and opportunities to work together would be the ethical choice. I also think most people would agree that the investment to grow all children well—to love them, talk to them, and listen to them—would be profoundly wholesome for everyone.

The Need for a Defined Judge

If the assessment process for carrots checks on how a carrot looks and tastes, we expect the consumer, the client, to choose the ones to eat. To apply that metaphor to the assessment of children’s learning, we must first look to the consumer, the client, whose interests ultimately matter. If a child is doing well, being creative, compassionate, and acquiring new dispositions and abilities, who sees what happens? Who cares?

The Audience That Cares

The people who really care whether a child is learning, growing, and happy are the child, the child’s family, the educators who are with them every day, the other children in that group, the other educators who know the child, and others in the community of the school.

Since these are the ones that care, any assessment of a program or a school should, of necessity, be addressed to them in a way they understand and find useful. If they aren’t engaged in attending to the assessment results, it’s a waste of effort. The form of communication of the results must intrigue them. They would also need an opportunity to participate and reflect upon what it means.

It’s obvious that those who know the child, who love the child, who value the child, and who are compassionate toward all the children, have a direct interest in each new accomplishment and would enjoy participating in discussions about attending to the truly important abilities and dispositions that portend a fully realized life.

Viewing evidence of their hopes and dreams for children, their own child and other’s children, touches the heart. The community becomes joyful and energetic. What a huge relief it is for a family to feel confident that their child is in a good school and doing well. Educators get to see their impact upon the children they love. It is exciting to contribute to a school where opportunities have been engaging for the children and to envision their carrying their strengths forward into their futures. Why should it be any other way?

Precision Over Time

Portfolios are a way to accomplish this by redirecting our assessment efforts. We change to collecting events of interest to the community that cares in order to create an opportunity for a conversation about learning. It could be too much to do unless the content of the portfolios is limited to a few streams of learning and change. With a specific narrow focus the individual portfolio can follow the child from infancy onward, gradually accumulating products, events, stories and reflections, becoming richer and more valuable year by year.

The history in an individual portfolio, when it includes a continuing record of the reflections of the audiences that care, grounds conversations among educators and families, sparks their participation, celebrates the uniqueness of each child, and supports their unique strengths. A portfolio of celebration can change a child’s life.

A Profound Result from Time and Effort

It takes work, of course. A shelf of portfolios inhabits the classroom. It becomes a prominent feature accessible at any time. The set of named binders reminds the educators, the children, each child, and the family (and even the funders) that this school for children cares every day about its essential values and goals. Evolution and change are the focus of work in this school.

Only the Gems

It works best if it is kept simple. Often what goes into a portfolio is a disorganized scrapbook that is hard to look through and difficult to understand. The core Item portfolio collects only key products, events, and learning stories, with the special inclusion of a standard form inviting reactions from the families and recording the child’s comments, too, becoming a growing record of periodic reflections.

A focused portfolio of what deeply matters to children and families offers the possibility of evolving the common work. Only certain items—the gems that make the greatest impact—should be included. I have seen twelve continuous years of content-focused core item portfolios maintained and reflected upon by the children and families. I watched the fascination and excitement of portfolio share days as it gained interest year by year. As little as two years of gems and reflections can change the culture of the school. It gets thicker every year. The reflections become reflected upon. This object the families pour over together defines the common purpose: everyone knows that they gather together to participate in this community where people flourish.

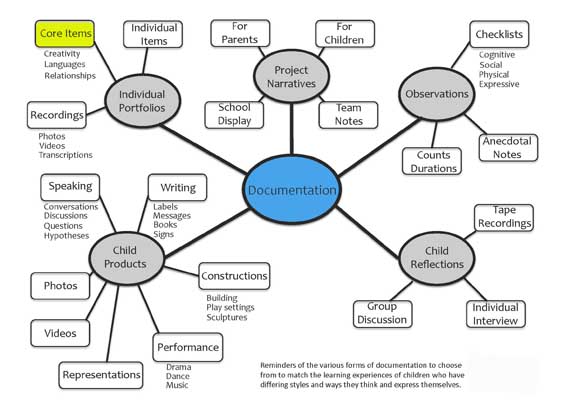

Windows on Learning, Judy Harris Helm, Sallee Beneke, Kathy Steinheim (1998) slightly modified with example tags and color, by Tom Drummond (2016) Documentation Web PDF

In the upper left corner of the diagram you see that a core item portfolio is a subdivision of all the kinds of documentation. Lots more can be going on. The core item portfolio has a narrow purpose of recording the strengths of this child over the years. Each year can’t be too thick: imagine 10 items over the course of one year. It is definitely not a disorganized dump containing every photo and every piece of artwork tossed in without purpose. The goal is to make it juicy.

—> Selecting Three Core Items

The challenge is to decide on the three categories of products, which can require many discussions and may take a year to dial it in. If it had four categories, the work rises exponentially, so I offer an example of three: Creativity (energy and courage), Language (expressive depth and breadth), and Relationships (compassion and cooperation). The categories become the handles on three suitcases of your choice. Each case contains a chronological record of this year of life representing that big idea. Since most of life is not gem-worthy, most things are not added to the portfolio—only highlights that are most significant for this child in this year of life and which might remain noteworthy for a lifetime.

Creativity

Creativity

Taking risks to try new things. Generating designs, theories and connections. Exploring new situations and physical challenges. Being a generative force. Acting with self-confidence at important times. Exploring unique strategies. Carrying intentions forward in time and complexity. Taking personal responsibility.

Languages

Expression in any of the Hundred Languages of Children, (dance, pretend, drawing, blocks, arrangements, clay, etc.), all the arts, oral language, written language, sign language, categorizing, sequencing, using symbols and signs. Roughly speaking, the child uses a medium skillfully to represent or re-present personal meaning in a way that communicates powerfully to others.

Relationships

Emerging events in the social world of relating to others. Acts of friendship, responsveness, invitations, parallel actions and cooperation. Courteous encounters with others as members of a classroom community, such as greeting, assisting, problem solving, conflict resolution, negotiation. Acts of compassion, altruism, listening, caring, and celebrating others.

Each time educators face the decision to include or not include an item they evolve clearer understanding of the reason why the event is significant. That is the process of becoming a professional.

—> Selecting a Long-term Format

Instances noted, photographs of works, interviews, observations, and reflections are

“captured” and converted to a flat format which becomes a cumulative record of the flow of three rivers—not everything ever made or seen, but key things captured and transferred to paper. If one uses a 3-ring binder, each item is punched and added on top behind the category tab. Page by page, educators create a chronological record from infancy to school age. The folio is portable, moving with the child in school and eventually residing with the family.

—> Including a Reflection Process

Periodically, say every six months, the child and their family formally review the gatherings together seeing a story of growth and change. At a portfolio sharing event, members of the family take a moment to write their thoughts voiced as if speaking to the child, using three reflection forms which are inserted into the chronology. Educators may add a page expressing their current thoughts to the child, too. The portfolio begins with an introductory explanation page, a file tab for each category, and a fourth tab to store the reflection forms. I expect someday we will have technology that could enable this to happen, but a book in hand is always an opportunity for a snuggle.

Creating a Democratic, Inclusive, Reflective Culture

This accumulating history of three rivers of growth, with periodic comments and reflections bringing back memories of the time, offers a unique view of learning in a culturally inclusive and celebratory way.

Making the effort to create a categorized space for repeated reflection upon learning and growing creates a shared culture of transformation and continuity.

Perhaps politicians might visit one day and read one or two of these portfolios and be able to grasp the benefit and vitality of this school for young children and their families. Later stories told of the events in that portfolio become undeniable evidence of doing the right thing for children and childhood.