Offering Information

I have mentioned before that we have three choices when something untoward occurs:

- ignore the problem

- somehow facilitate the children taking responsibility for solving the problem

- assertively take responsibility to stop such problems.

We have covered the third one on the Acting Assertively page. We take responsibility and take immediate action when actions are clearly non-negotiable. Now we address the second one. I know it is possible for the children to take care of almost all other problems that arise, and they seem to like taking charge, providing solutions, and providing care for each other. This necessitates a responsibility transfer from you to the children, so they can gradually learn to do it. This is how to create a culture for that to grow.

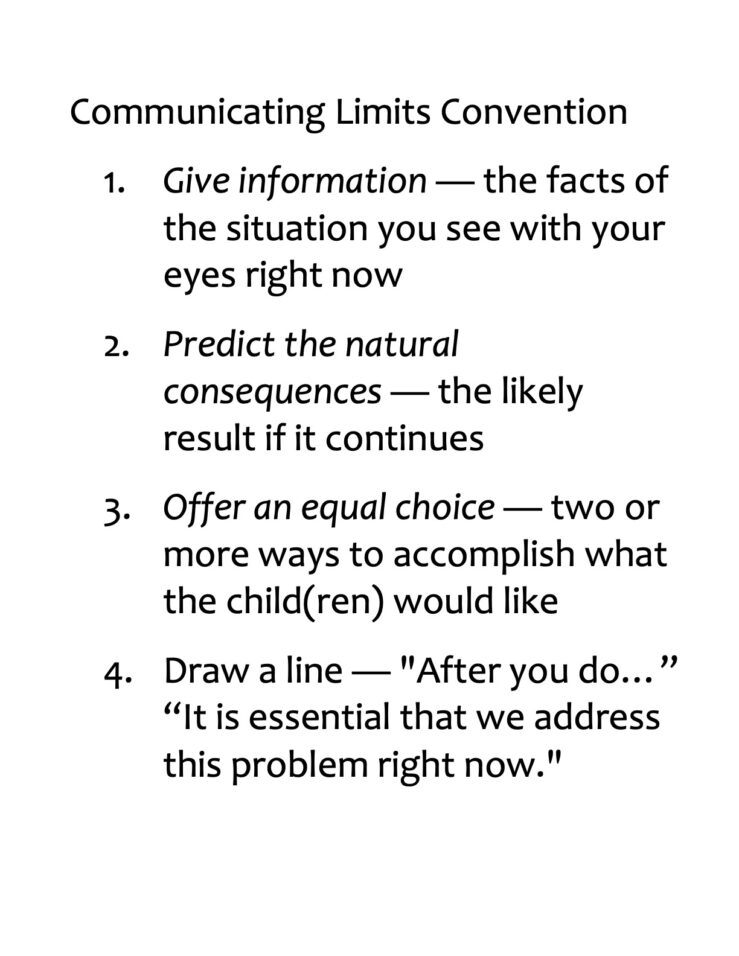

Communicating Limits Convention

I have built a convention in the sense of a normal way to deal, an expected norm of conduct, or a customary way of acting. This becomes part of the culture of a school or a family if the adults model it over and over again. The Communicating Limits Convention is a guide which I have found orders the kinds of things the leader says in dealing with a troublesome problem.

For example, let’s imagine a child is pouring water from the water table onto the floor, either accidentally or on purpose. Water on the floor isn’t really horrible, but it still presents a problem for the floor or for people walking by. One could simply ignore it, the first bullet at the top of the page, or one could create a space for the child or the group of children to take responsibility for dealing with it.

For example, let’s imagine a child is pouring water from the water table onto the floor, either accidentally or on purpose. Water on the floor isn’t really horrible, but it still presents a problem for the floor or for people walking by. One could simply ignore it, the first bullet at the top of the page, or one could create a space for the child or the group of children to take responsibility for dealing with it.

Ways to say things, ordered from very light, to light, to moderate, to firm:

1. Give Information

Offer facts (not emotional reactions) about what you see with your own eyes or hear with your own ears right now. Included in the facts are the agreements shared by everyone in the group. Then wait for the child to respond or rectify the problem. “The water is running onto the floor.”

If that works, the job is done; if not, then we go to the next level.

2. Predict the Natural Consequences

Outline the likely results if the current situation continues. “Someone may hurry by and slip.” “It can run under the cabinet and harm the furniture.”

3. Offer an Equal Choice

Offer two or more ways for the child to rectify the problem, or accomplish what they would like, in an appropriate way that you could agree to. “You might use a towel, block the area off so no one steps there, or make a warning sign WET FLOOR. You can choose a way to deal with it now.”

4. Draw a Line

“We have to address this problem before you go on playing in the water.”

“After you take care of the problem you can continue to play.”

Practice

This makes a great chart in the classroom, so everyone communicates in this sequence. The more often it is used, the more likely it is that the children will take action when one makes an observation in the first step. I offer you a PDF of a wall chart that can be posted in handy places.

I also offer a card game of 10 scenarios for people to work together to generate what to say in each of the four consecutive steps. It consists of a two-page PDF which you can duplicate, cut into equal sized strips, and place in an envelope. Limits Game

I also offer a card game of 10 scenarios for people to work together to generate what to say in each of the four consecutive steps. It consists of a two-page PDF which you can duplicate, cut into equal sized strips, and place in an envelope. Limits Game

After you have practiced what to say in these situations, here are common ways to begin the four different comments:

I see…

What may happen is…

You may do… (cool idea) , or you may… (another cool idea0

You can only do… after you…

Your Emotions Are Yours

In #1 Give Information, people may more readily talk about their own feelings instead of what they see or hear: “I don’t like it when…” “It makes me sad when…” Those comments are not facts; they are feelings. Each person has responsibility for the feeling they have. If you talk about your own sadness, disappointment, or hurt, as if it is caused by others, you lay a guilt trip on them. The goal here is to avoid talking about your own feelings and talk about what you actually see and hear. “Paul’s block structure is broken.” “Four people are trying to wash their hands.” What you see is articulated as a fact: facts are present and actionable — emotions are not.

The Challenge: Truly Equal Choices

In #3 Offering an Equal Choice one has to be creative instead of angry — on-the-spot fast thinking. It is difficult to be present enough to think on your feet to invent options the children want, in other words, aligned with the child’s intentions, not your convenience.

One’s first thoughts are often alternatives based in one’s own solutions: “You can either clean that up or leave the area.” “You have a choice: either clean that up or I will close this area.” That’s the police talking: do what I say or go to jail.

That is why this challenge is called an equal choice, to the extent possible, each alternative you generate provides an opportunity equal in value to what the child was doing—equal from the child’s perspective. You offer an appropriate solution to the current problem that kind of does the same thing but more appropriately.

Summary Document PDF Leadership & Care

Cynthia Willmarth, Mauna Lani, Hawaii

contributed this story…

Living by the Rules… or Not

I remember when I took down the “rules” in my classroom. They really weren’t that harsh…be kind, use your words, run outside and walk inside, put away your choices after you use them…but, they were the rules, my rules. They were my security and my false sense that my class would be orderly and efficient and tidy (Isn’t that what a good teacher’s room looks like?) A room without rules…nonsense! Or, so I once thought.

The children walked in to the “room without rules” Monday morning. Not one of them mentioned that the “rules” were gone. They went about their playing without much notice at all to the fact that there was a blank space on the wall. But the change was definitely there, not in the classroom, but in the attitude of the teacher. A symbolic gesture of taking down the rules, I discovered, had created a silent but powerful change in this teacher. I had made a choice to teach in the moment, to help children begin to learn to negotiate, to problem solve, to effectively communicate their feelings about what was happening in the moment it was occurring, and to make decisions. I didn’t know the direction I was going, but I knew where I wanted to go. I had to TRUST in the children. I had to let go. It was about everything that I really wanted to nurture in children… the ability to think beyond the box in front of them.

The children walked in to the “room without rules” Monday morning. Not one of them mentioned that the “rules” were gone. They went about their playing without much notice at all to the fact that there was a blank space on the wall. But the change was definitely there, not in the classroom, but in the attitude of the teacher. A symbolic gesture of taking down the rules, I discovered, had created a silent but powerful change in this teacher. I had made a choice to teach in the moment, to help children begin to learn to negotiate, to problem solve, to effectively communicate their feelings about what was happening in the moment it was occurring, and to make decisions. I didn’t know the direction I was going, but I knew where I wanted to go. I had to TRUST in the children. I had to let go. It was about everything that I really wanted to nurture in children… the ability to think beyond the box in front of them.

What was so powerful, and to me, has become one of the most fascinating aspects of teaching, is how quickly the children took ownership of their classroom. They really started to be aware of their surroundings and of each other. They took notice; they were observant; they were interested. Chaos? No! Not a bit. We talked a lot. They talked a lot. The incredible insightfulness of young children was revealed to me and I learned right along with them. Sometimes it was (still is) messy. I have no idea what conflicts we will encounter with each day (isn’t that life) but I am sure that we will problem solve a lot, every day.

Of course, I am still the authority in the classroom. It is my job to keep children safe. It would be very unwise to believe that children are capable of handling all of their situations on their own without adult intervention from time to time…We move in that direction though. My goal is to help these children become adults who “will” one day be able to creatively and compassionately handle situations without adult intervention, which is certainly not always typical of the adults in our society.

Getting rid of the rules has definitely been one of the biggest growing experiences for all of us. Certainly a chance for this teacher to, once again, be a reflective practitioner.

Toddlers

Theresa from Palo Alto, California, asked me a question by email, and I thought her example might help illustrate what we have covered so far.

“Can you advise the best way to bring down some of the ideas for younger children (15 to 24 months of age)? For example, with toddlers, taking something out of another child’s hands is very common. Would you suggest I simply watch and not intervene when this action occurs? Other than offering the child who no longer has his item, a similar item, should I say something to the child who took it out of the other child’s hands? What do you suggest the explanation be to an offended parent who is looking on? I’m just picturing if I do not correct my child as he continues to take something from another child, it might appear to others I am not “minding” my child. Likewise, when another child snatches something out of my child’s hands, my child screams. I take this to mean he is upset. What would you suggest I say to the other child (if anything)? What about when a toddler knocks down the work (say, a tower) of another child? What about when a toddler feels threatened by another child being too close to a toy he’s playing with and strikes (hits) another child when he comes close? “

Dear Theresa:

I want to work through “taking something out of another child’s hands” as an example of all three problems: taking, destroying, striking out. In all these cases I have no idea what you should do, but I trust that you do. You are the only one who knows what to do because you know the children, have a relationship with them, and are present to the nuances of the moment. All I can do is offer some guides for optimizing your actions when a problem occurs.

1. Decide whose responsibility it is. Sometimes it might be your responsibility as when child takes another child’s food or toothbrush. Taking toys or knocking stuff down often is the child’s responsibility.

2. Depending upon that decision, you can (a) act assertively if it is yours to deal with, or (b) offer information if it is theirs to deal with.

If something is sitting on the floor unused, it is unseen. If it is put to use by someone, suddenly it becomes attractive. Knocking over is attractive, too. If the child has intentions to continue playing with something, the opportunity to keep playing might have to be communicated with a scream or something. These ways of being are natural.

Could you not intervene? Possibly. I was just visiting a school a few weeks ago where I saw this happen many times. Children took things from other children, and it did not seem to matter. The takee simply let it happen and did something else. I thought it was rather respectful, because there was also a communication that happened at the same time. “I want this.” You can always try not fixing it but describing it as a research project to see what happens. It might be different with different children. In conducting research such as this I love video, because I see more in the recording than I do at the event itself. This is the kind of research I have done.

I am not a big fan of continuing to offer distractions to older toddlers, which are so useful with infants and young toddlers. I don’t value children being enticed by someone with more power when they obviously have an intention thwarted. I think we all know the difference between try this try that try another and when a child intentionally wants to cause an effect. I value a child’s freedom to act in the way she wants as a powerful, capable individual.

I always like being informative, following the guides of Enterprise Talk. You can offer language for the takee to use. “Mine.” “Hey!” “My turn.” This feels like floating a cartoon language balloon with words to use or not use as the child wishes.

I always like being informative, following the guides of Enterprise Talk. You can offer language for the takee to use. “Mine.” “Hey!” “My turn.” This feels like floating a cartoon language balloon with words to use or not use as the child wishes.

If the takee communicates that being robbed is wrong in an appropriate way — verbally in words, physically in actions, or vocally in sounds — my attention shifts to the taker: I provide information there. “She wants it back.” “She is telling you she was using it.” “Oh my. Oops.” “You can trade.” These kind of statements are different than imposing an adult rule, such as, “You have to ask.” “Use your words.” Adhering to the guides of Enterprise Talk, the last two statements are directions — bossy — and prohibited, as the guide says, to give you time to think of another way.

I like treating the classroom materials as if they belong to the community not to individuals. Individuals may be using particular items, but they are not really theirs. The members of the community can work out how to use the community resources. Food on Meagan’s plate, however, does belong to her, as does her toothbrush and items in her cubby.

The idea of “correcting” a child is using power, otherwise it would not be thought of as correction. Managing power is essentially what I address in the topics of Leadership and Care and Enterprise Talk. Being aware of disarming one’s own power seems to remain a hurdle for people who think of themselves as “teachers” rather than facilitators of a community. You don’t have to “teach” in your job; rather you be with, care for, inform, and lead. I think of this hurdle as part of the culture of USA, which promotes individualism and obedience as guiding concepts rather than cooperation and community. Other cultures hopefully don’t have this problem.

I think the screaming response by the takee presents the most challenge; the takee screams in a context where you have decided it is the children’s responsibility. The scream often draws you into the situation whether you want to or not. Now you have two less-than-optimal behaviors at the same time: taking and screaming. Neither child is in the “right”. You are in a box.

1. What not to do

If one follows the guides of Enterprise Talk, one tries not to reward less-than-optimal behaviors. Narration is one of the most powerful rewards one can offer, so narrating the undesirable behavior — “You took that.” “You are screaming.” — leads to more of the same over time, which may not be your goal. In my view, narration of the less-than-optimal is worse than saying “STOP!” which I rather like BTW.

2. Personal perspective

You can feel, as I have very often, that you have a responsibility to appear as if you know what you are doing, especially in front of observing parents who also happen to be funding your employment. If you want to look good, you might think you cannot appear to be uncertain of what to do. But the deeper understanding is that we are all uncertain and if anything is a guaranteed problem it is our own ego. There are many paths towards the ideal of open, honest integrity. Great educators have all done personal work to become authentic, present people. Gradually I have learned — which Carla Rinaldi has voiced so very well — that being uncertain is a value; uncertainty and playfulness are the motivating factors behind both research and the provision of optimal environments for growth. Maybe waiting to see what happens is research.

3. Provide information

If one follows the guides of Enterprise Talk — while avoiding narration — one has two options: Descriptions, such as “Uh oh, a problem.” Subjective talk (I’m the subject), such as “Sometimes that happens to me, too.”

4. Listen

If one follows the guides of Active Listening, one starts with paraphrasing, even when the children appear to not be able to understand. Paraphrases: To the taker: “You want that.” To the takee: “You want to tell her don’t.”

Both #3 and #4 may seem to complex for such young children, but I assume what I say to toddlers, when simply phrased, makes emerging sense to most children. That amazing receptive part of the brain is working full time to make sense of things, good and bad. It takes maturity for the neural pathways to connect the receptive language understanding area of the brain with the expressive language producing area of the brain. The lack of a fully functioning connection between the two areas does not mean the child does not understand. Since each area is working separately on its own, I trust that understanding is being constructed within. Life has its ups and downs.