Talking to Children About Their Art

Can you tell me about your painting?

How did you do that?

What part did you enjoy the most?

How do you feel when you look at it now?

Asking children to talk implies the painting they just made is not sufficiently expressive—possibly missing the point of art. Works of art communicate directly to something within us, expressing what words cannot. The viewer receives an experience of the work itself, which requires a receptivity to the nature of the medium as well as offering a response to the child. If we care about communicating the nature of art, we can model that for this budding artist, like Nathan here, who is requesting our regard.

Nathan, 4 years old

“Look!” Nathan turns and says to you. It’s your turn to do something.

He asked for attentiveness, where, in most cases, he hears…

Oh, how beautiful. (but that’s a judgment; beauty may be not the child’s intention)

Can you tell me about it? (but that’s a press for words that may be hard to say)

You worked really hard at that. (but that’s often a habitual, off-handed remark intended to be supportive)

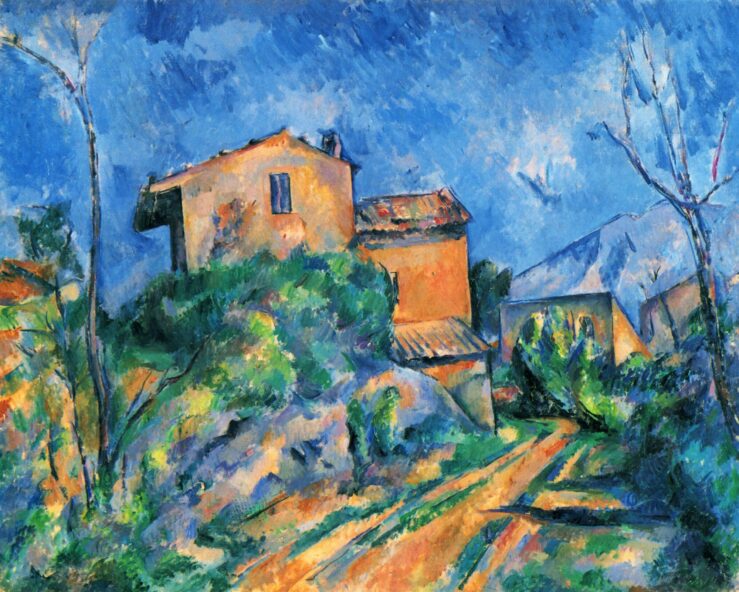

Paul Cézanne, 56 years old

Maison Maria with a View of Chateau Noir, 1895

In 1895 you stand beside Paul in France, You note Maison Maria on his easel. To be polite you say…

Oh, comme c’est beau.

Tu peux m’en parler ?

Vous avez travaillé très dur.

Comment vous sentez-vous, Paul, quand vous le regardez maintenant?

He might be somewhat shocked by what you were doing.

Appreciation

Art appreciation, as an idea, expects an observer to make an effort to reflect on the personal experience of the work, with attentiveness to the context of its making. The act of comprehending art takes the observer’s time: to stop, to view it with openness to one’s emotions, to identify what one is responding to, and to regard the intention of the artist.

Why not bring art appreciation to a four-year-old’s work as well?

Being Intentional When Responding to Children’s Artistic Expression

Authenticity and integrity are the only guides we have as educators of young children. The only ‘best’ we know is to be genuine and act in accord with our values. Each in our own way, we bring precision to bear on how four-year-olds, like Nathan, come to view their art. Acting decisively in this moment we influence their perception of what they are doing when they create in this way. We gently challenge them to become aware of the ways their impulses, fresh in their memory, created results that are expressive to others.

An authentic response of a caring adult to the work of the child—especially between the ages of 3 and 6—may affect their awareness and intentions in the years ahead. If they discover the affordances of art as expression at that stage of life when they are acting freely and spontaneously, they may use the medium unencumbered by the social expectations that come later.

Protocol for Responding to Children’s Art

Normally I leave children alone when they are painting. I like to see them interact impulsively with what the paint has done. Painting, as opposed to clay, is an all-consuming process of freely chosen acts made in response to results of one’s own causing—over and over again. It seems to me expressiveness in clay can continue alongside a casual conversation with others, which isn’t true of painting. You can watch how all-consuming painting is. At the end, we can talk.

When a child turns to you to look at their work, with the path of creating it fresh in their mind, the challenge is to be present in care and leadership. Like all the other protocols at this site, I invite you to make yourself a note card for your apron, so you can try it out. In these ways you can highlight how art communicates human-to-human, which isn’t available in words.

Three parts to this listening protocol: stopping, hearing the child, and responding to the work.

1. Stopping—Becoming Available

I pause, wait, and listen first, keeping my impulse to say something under control. It usually takes 10 seconds for my whirring thoughts to stop and begin to pay attention. I tell myself to stay silent, counting slowly to 10. I then start looking closely at the work, taking it in. I want to be empathetically available. Right here. Right now.

2. Hearing—Tuning into the Person

Having a pleasant conversation is not necessarily the focus for this moment. Now is time for this work of artistic expression and the artist. If the child wants to say something, I will find out by waiting. Usually it takes anyone at least 10 to 15 seconds to transition from the non-verbal intensity of painting to finding thoughts to share. If the child says nothing, you still have communicated a closeness and an interest.

If the child does say something, I recommend what I call the Responding Convention, which I discussed in other contexts: Best Practices in College Teaching, Responsiveness, Active Listening.

These responses maximize the possibility for further communication.

1. Paraphrase

I restate the child’s underlying message, confirming I understand what they mean by trying to say the same thing from my point of view using totally different words. I want to check we have communication: sending—receiving—confirmation.

Nathan: Look! Tom: You want me to see.

Nathan: I’m done. Tom: Ready to move on.

2. Parallel Personal Comment

As an alternative or a subsequent step I can reply with something from my own experience that exactly corresponds. I must match the topic exactly.

Nathan: It’s a cave. Tom: It looks dark in there.

Nathan: It’s a cave. Tom: I’d be scared.

3. Responding—Listening to the Work

Two parts here, also. First, objective comments that focus on those aspects of the media that can be regarded and, second, sharing a personal, subjective experience of how the painting speaks to me directly, in the way art does. I find it is worth spending the time to attend to the work, really feeling it, before talking about it to the child. I use these guides as topics for a response.

1. Objective Comments

Painting has its manipulable qualities seen in the application of paint and the results on the paper. (Clay has another set of qualities to regard, wire still another. All media are different.)

In no particular order:

Brushwork: quality of line, weight, texture, direction, fullness/dryness of the brush, energy conveyed in movement.

Color: fully descriptive names for colors as they can be found in nature, how color balances on the page, the ways colors interact (blending, overpainting, and mixing), receding colors, advancing colors, complementary colors, tints, shades, colored grays and browns we see in life versus the colors in the paint containers.

Mass: use of space on the page, relationships of spaces, relative sizes, balance, negative space, the travel of one’s eye

2. Subjective Comments

As in other discussions at this site, I use the word subjective to mean I am the subject of the sentence. Sharing one’s experience of regarding an artist’s work communicates to the child what art does for the human spirit. Here is an opportunity to convey something of the impact the work has on a sensitive observer of the child’s work. Usually these are brief comments that allude to what makes art unique.

Personal associations: what immediately comes to mind, first thoughts, “Reminds me of…”

Personal experience: attending to one’s emotions as if personally immersed in it and then describing one’s feelings, describing an experience where that same feeling was created.

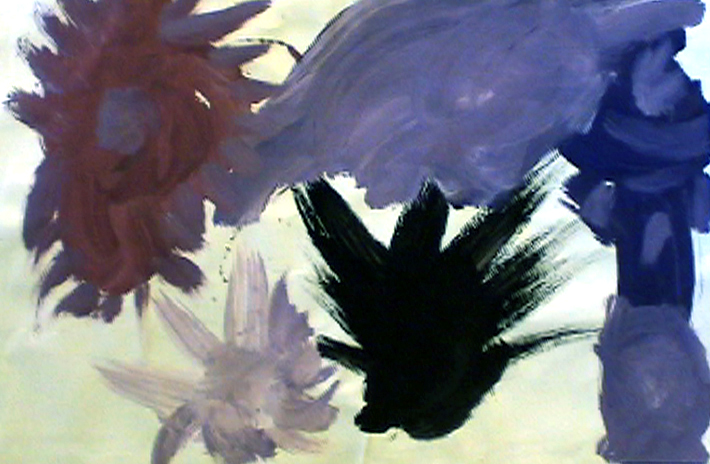

Below are protocol examples applied to Nathan’s painting.

Objective Comments

comments about brushwork

I can see how you moved the brush differently in different areas of the painting.

You spread the blue evenly, so smooth you can’t see brush strokes, so the color is what matters.

Around the edges, the brushwork energy is more noticeable than the color.

The brush strokes in the dark areas are bold and slow.

These drip lines and dots jump at you, because they are overpainted; they stay on top.

comments about color

I see the colors of green apples and the colors of clouds.

The deep blue of unmixed color right from the cup dominates the painting.

Those dots of yellow come forward like lights.

The blue color looks like it is behind everything, as if it were a hole we are looking through.

Where you brushed a little white paint into the blue, the colors blended; in blending, you can still see both the white and the blue.

Where the blue and white mixed (top right), you don’t see the white anymore.

The white tinted the blue; that’s what the word “tint‘ means: the same blue hue remains, but it’s lighter.

Where yellow mixed into the black, no yellow remained. A little bit of black powers over all of the other colors.

Black is strong; yellow is weak.

Adding a little black made a shade of blue, like it was seen at night.

I can understand how this muddy brown was made with yellow and black, but I have no idea where the rust color came from.

comments about mass

The page is filled entirely; the colors go right to the edge of the paper.

The white drip line connects one side of the painting to the other, like a string tying a package.

We see four main areas: the white center dot, the dark tumbling middle, the sea of blue around, and the edge frame of lighter mixtures.

Subjective Comments

These are best when brief. The intent is to convey how a viewer is affected by the work.

personal associations

“It reminds me of riding a bicycle on a sunny day: everything is beautiful and happy, then crash and pain, but you get back on and ride.

personal experience

“It makes me feel like there’s trouble. Something isn’t very good. I’m still happy, though. I’m not getting upset.”

“It’s like being hungry.”

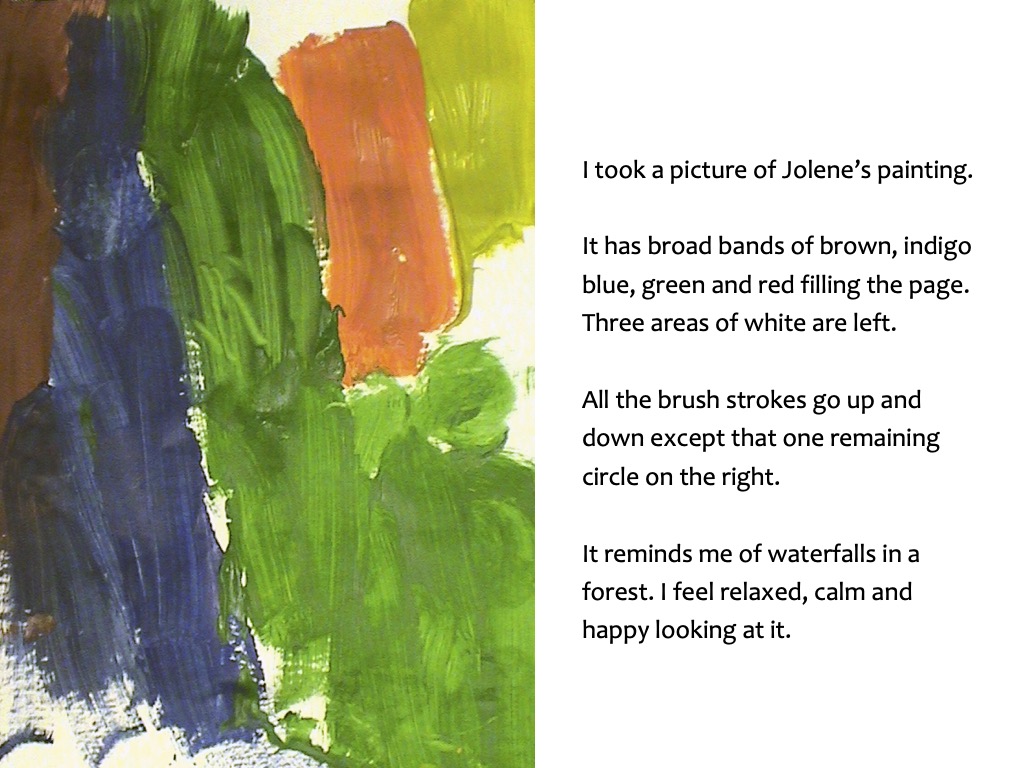

Here’s an example from the Examples of Learning Stories page from the Jolene materials shows this convention applied to her painting. Note how brief the comments are. It’s not an art lecture.

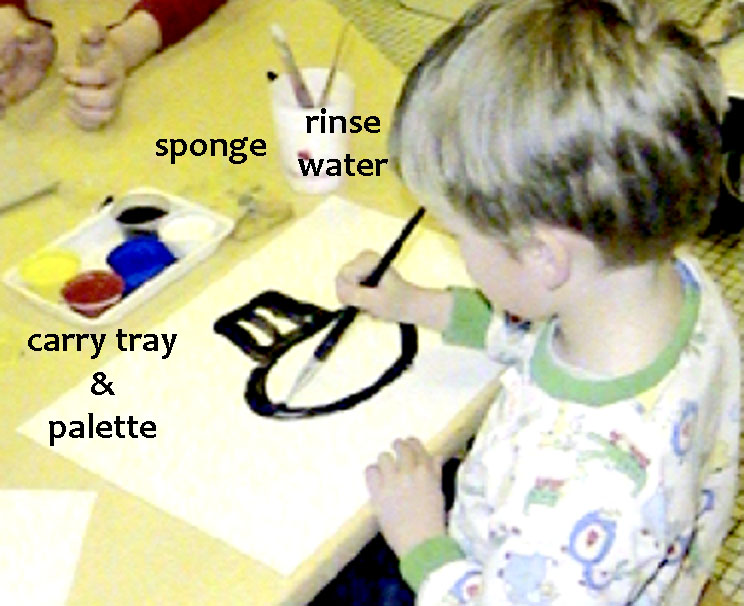

Tempera Paint

Here are Jolene’s painting and Nathan’s side by side. Note the difference in the quality of the paint.

Jolene was using a kind of tempera that is washable and comes in premixed colors. Nathan was using a premium tempera from a major online supplier. Note how the depth of the color in Nathan’s retains its vibrancy when dry. Note, too, that the paint Jolene was using does not blend or mix; when one color goes over another it stays on top and no new color is created like Nathan’s apple greens and deep browns.

I care about providing the tools that work, like paint brushes that hold enough paint for a long line, color that excites the eye, paper that is weighty enough to carry a thick coat of paint. Great art materials attract children back another day to find that same excitement.

I think the work that preschool children do with tempera paint might be the most creative works of art they make in their lives. Children this age have both the ability and the unfettered freedom to try what comes to mind. In the beginning they explore the medium and its properties, but once they become intentional in action, they become less of a scientist and more of an artist.

Art at this age is almost magical. Art enables children to discover what they can do and who they are with a precious immediacy that can startle the mind.

Presentation of Tempera

2 oz portion cups so impure leftovers, like the yellow, can be discarded;

choice of two brushes, long handle or short handle;

a tray to carry these awkward bits and, possibly, a mixing palette if the tray were white;

red, yellow, blue primaries for color, and white and black for tints and shades;

(cyan, magenta, and yellow as the primary triad might mix better, like in printing, but I haven’t found cyan paint; turquoise doesn’t work.)

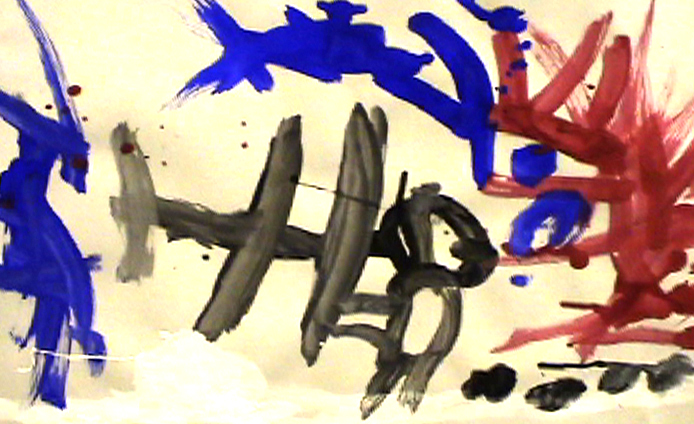

Exercises for Protocol Practice

Objective qualities: brushwork, color, mass

Subjective comments: associations, emotional experience

1

2

3

4

liquid watercolor

0.5 oz portion containers with a very small amount of liquid watercolor

cut down sheets of 140 lb. student grade watercolor paper

one taped to back of a tray and another taped to the front

children start with the front side and turn it over to paint the back paper

container of water

brushes #0 and #2