Download public domain PDF: Allindicators

Indicator Checklists

It doesn’t take long for educators to learn how widely different children are and how the ages vary when abilities appear. It’s always a joy to see children grow. Experienced educators, who have seen many children grow up, often love the little emergences of new abilities and inwardly smile.

The very experienced have learned to attend to certain “marker” abilities that let them know that children are doing fine. For example, when a child calls other children by name or sees what another child needs before they ask, the educator becomes confident the child is both socially adept and attuned to others—abilities that will benefit them all their lives.

New educators and caregivers may not notice these small good things. It’s hard to see every child when one is moving from crisis to crisis. Problems are always easy to notice; noticing emergence is gained through experience. Emergence doesn’t shout itself out, so it’s easily missed when there is so much to attend to.

I wanted to make sure I saw all the children, not just the most noticeable ones, for my data showed me that teachers attend mostly to the same 30% of the children. I developed this method to ensure that my noticing included every child across the major skill domains.

Assessment Informs Practice

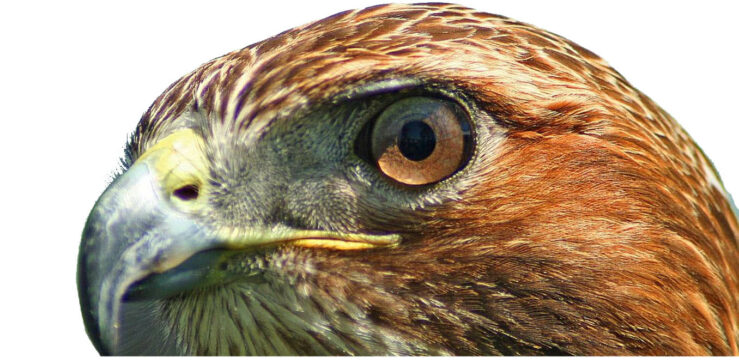

This is not a normal variety of checklist, where a specific item decided by someone else has to be checked off to “prove” learning was happening. Instead, these four checklists are a bird watcher’s notebook: an observational record in hand of the birds one has seen, a record of my own accomplishment. It’s not about how good the birds are. The record enables me to look for the birds I, personally, have not yet seen—assessment that informs practice.

The Indicator Checklists examine learning: the emergence of new capabilities over time.

I’ve been collecting key abilities ever since I first started working with children. At the beginning I was unsure what I was aiming for, so I thought it could be important to find out. It’s not easy to see learning at the time of its emergence, the very time that was most important for a teacher to see. It was easy to see the marvelous capabilities of highly skilled children. Their successes weren’t random acts; they somehow learned these skills, which I wished for every child. In order to investigate this problem, I recorded the skilled children, and I showed them to my classes, so we could watch them together to identify the capabilities that mattered. I used the lists we evolved to check on the children in subsequent years, gradually expanding into the expressive arts and physical skills.

Expanding Opportunities

I found that I was creating new kinds of opportunities for the children when their checkmark boxes were empty. In this way I check for what I didn’t see. I also found the children I had failed to notice.

I found all of the families liked knowing that I cared, which led to adding color codes to add a sense of time without having to record a date.

It has always felt like I have had to do something for a year or two, before I became confident in carrying it out and have discovered its value. Indicator Checklists proved well worth the time. This pursuit of empty boxes honed my ability to see every child, not just the ones at the forefront, because I learned where and when to look.

Gaining Experience

I have helped others start this, too, so I have a bit of background to say that it takes at least two years to train the eye. As all teachers know each group of children is different, so a second year of checking boxes on each child, marking through the seasons, offers further complexity.

I found I could see better after two years of diligence. I could confidently spot those children who were trucking along just fine, so I marked off most boxes for the self-evident ones and focused my attention upon those I couldn’t see. That proved to be the ideal way to use the checklists; it minimized the record-keeping burden yet maintained my attentiveness to collecting specifics to show their families and, by the way, direct my camera lens in the right place at the right time to capture emerging abilities for Learning Stories.

Like everything one learns, systematic practice helps one find out what you don’t know you don’t know, the problem we all face as teachers. The ability to see emergence in as many dimensions as possible becomes a step up in professionalism, worthy of a wage increase, I would say.

I invite you to try the Indicator Checklists long enough to discover what it has done for you in becoming the educator you would like to be.

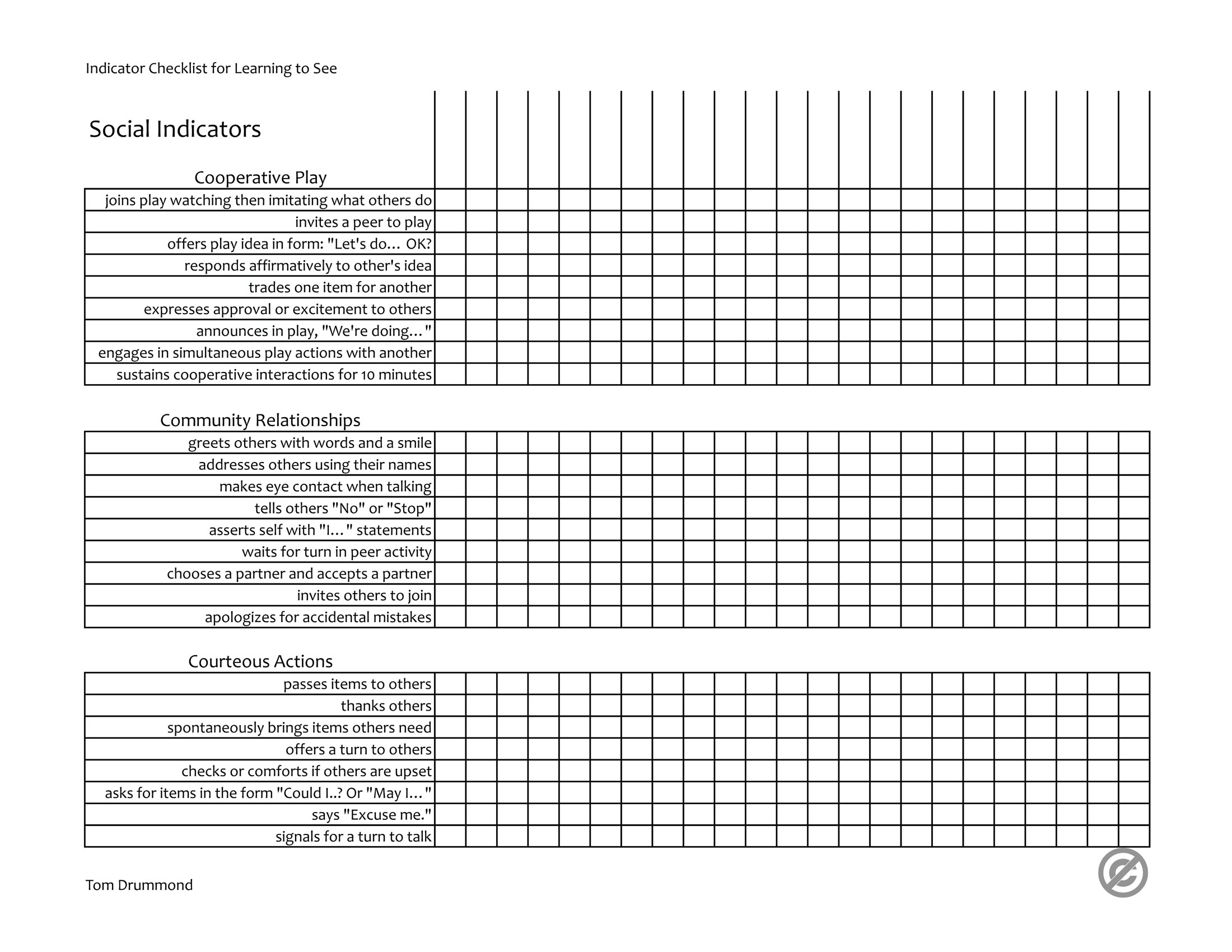

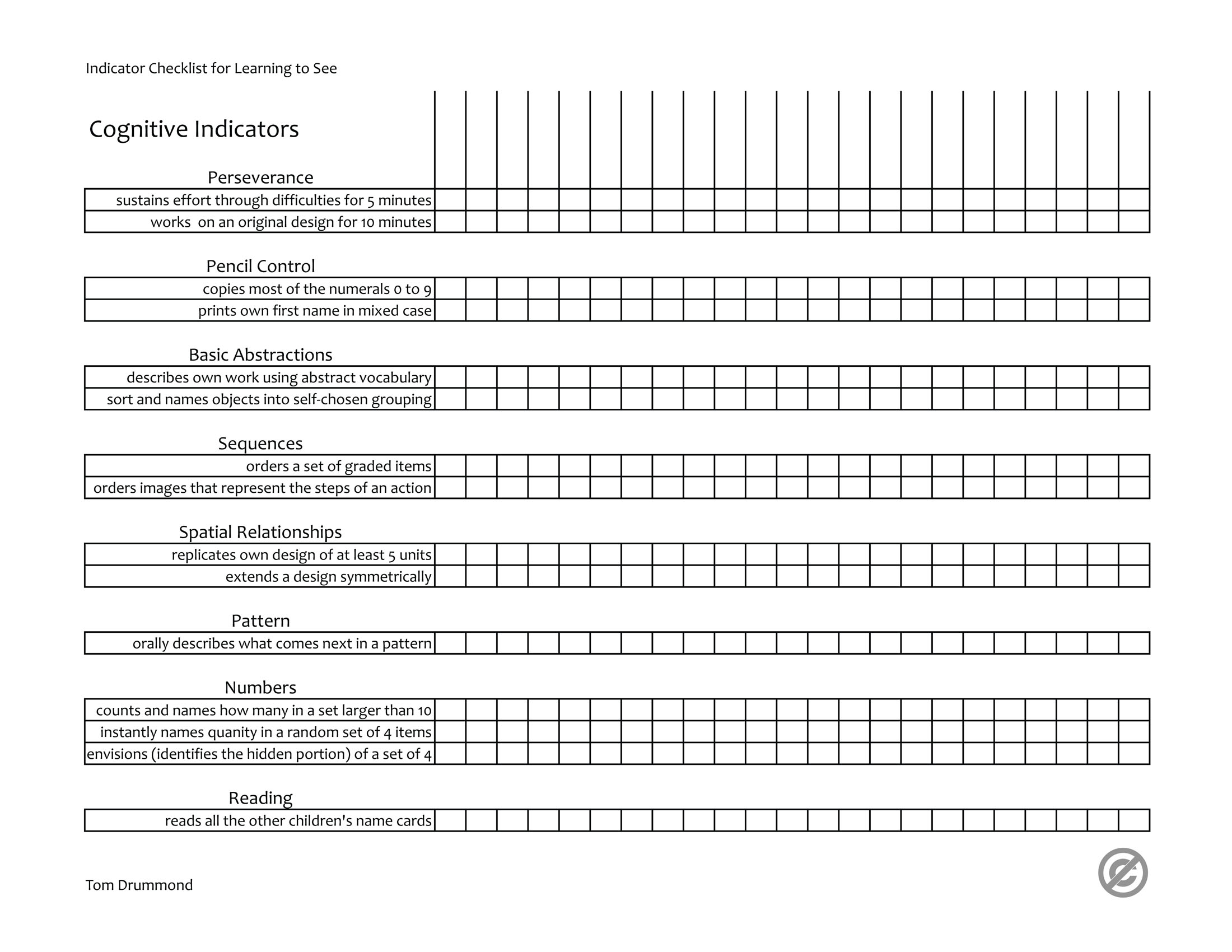

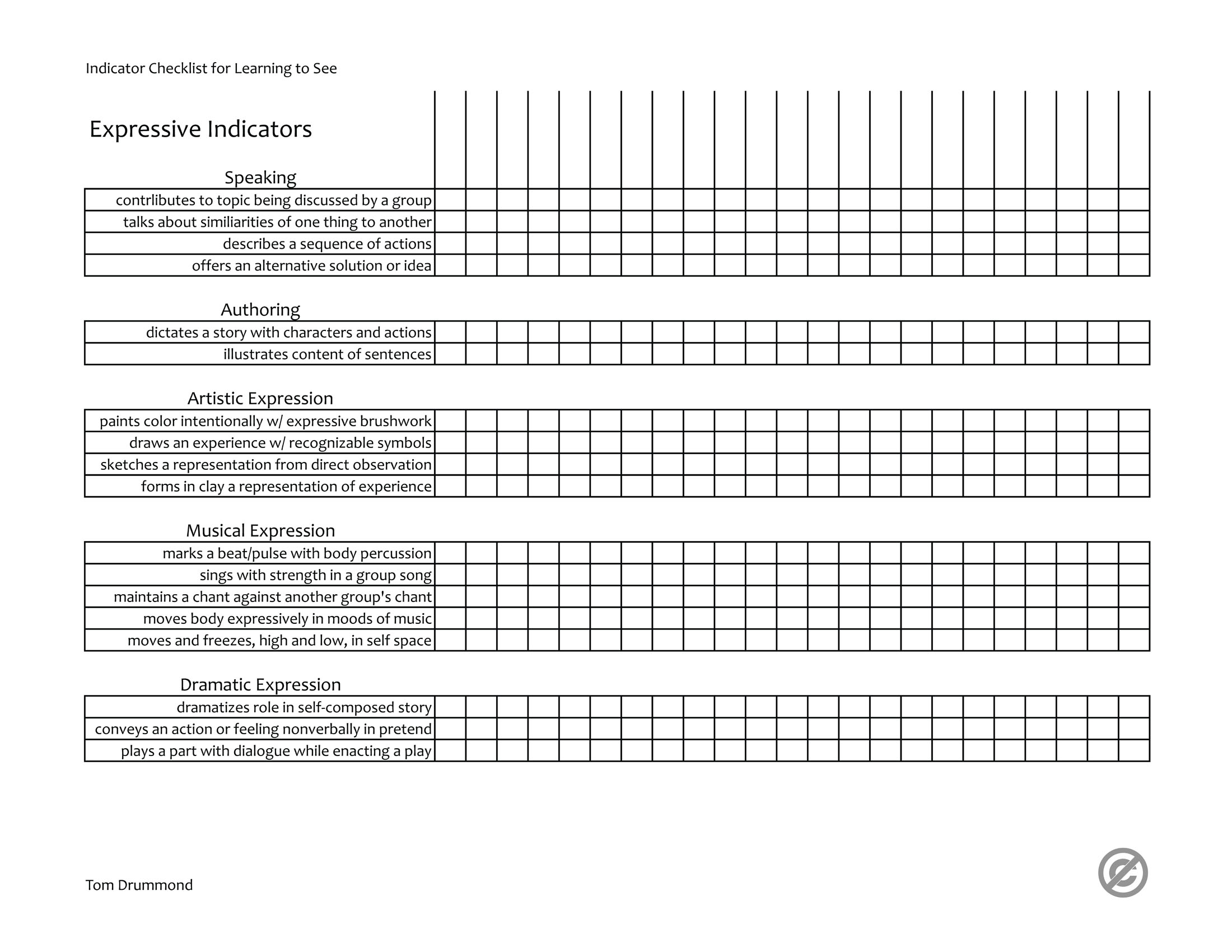

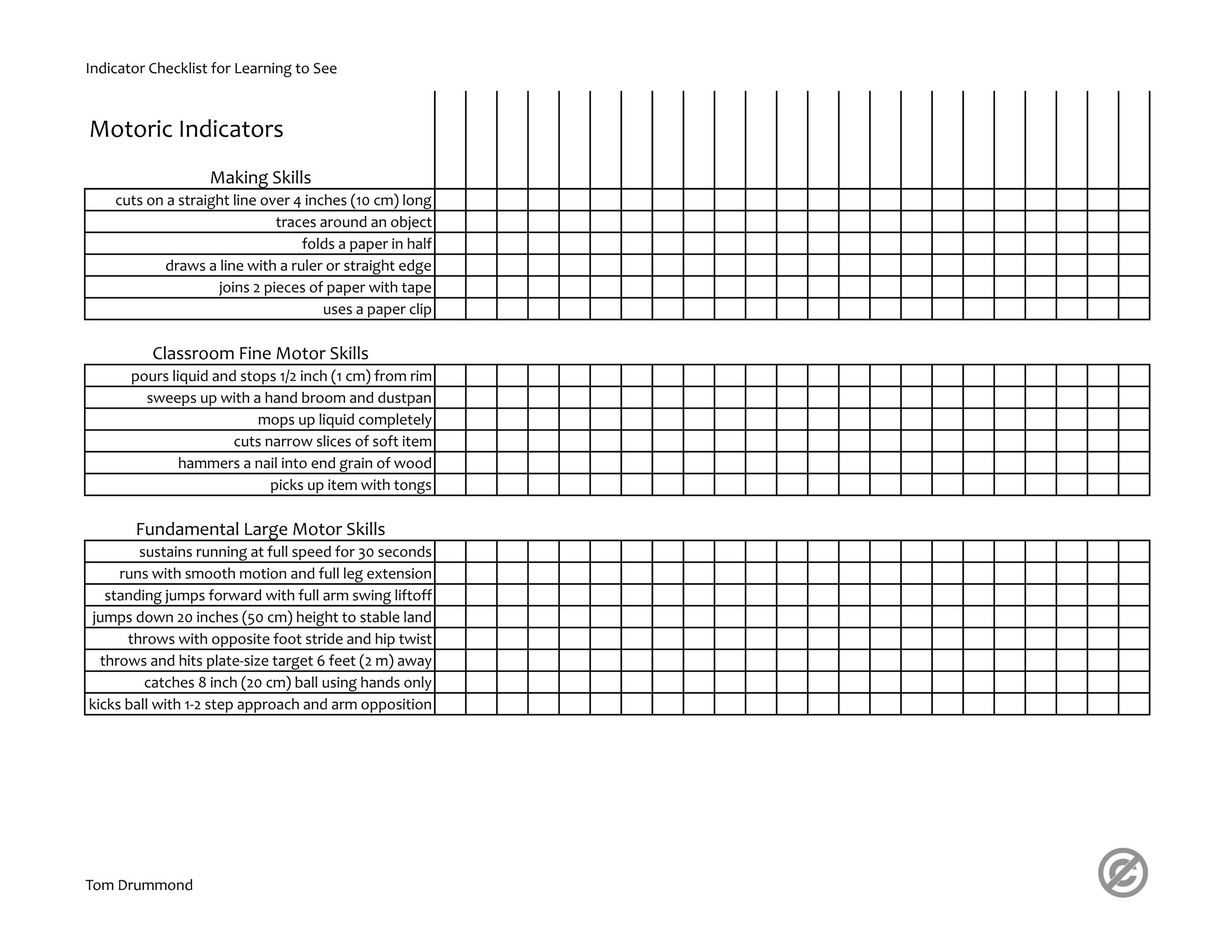

Social, Cognitive, Motor, and Expressive Abilities

These four pages of indicators address general categories of competence which emerge in differing ways at different times from toddlerhood to common school age. These lists don’t describe learning or have any utility for comparing children. Their validity, however, can be confirmed through one’s own observations. The charts list sets of abilities I found significant, in categories that made sense to me, independent of developmental timelines or particular ages.

Whether or not a child masters any single item is irrelevant. These are records for you, so you get to decide to check the box that indicates a child demonstrated the item to you—to your personal satisfaction. Once you mark the known, as seen by you, it’s over. You saw a robin. That’s done. The check allows you to turn your antennae in the direction of the next unknown, looking for a bird you have not yet seen. You aren’t looking for robins anymore.

Ruby jumped over a bucket.

I’ll check off Ruby. √

Thumbs up girl!

I see eight children have unchecked boxes for jumping over something.

Hey, DeShawn, Ruby jumped over that bucket. Can you believe it?

A missing checkmark, an open box, indicates either (1) the ability has been unseen or (2) the ability is not present so far. Empty boxes indicate the need for attentiveness.

Mary Elizabeth has almost all her boxes checked, but Johnny has only two. I’ll watch Johnny more carefully today.

When you know what to attend to, you can somehow create the conditions that might allow that ability to emerge and be observed.

Greets others with words and a smile. Johnny’s box is empty. I am going to make sure I greet everyone today with words and a smile and watch if Johnny starts in, too.

Maybe Johnny will start greeting others at his own initiative several weeks or months from now. Maybe not. You never know when others learn something unless you watch.

Moreover, you get to decide whether an item is important or not. You can always choose to leave something blank for any reason you wish. Say, for example, you know Suzie and her family; we are the team that knows her best. She is quite something.

I checked off all the items for the really amazing Suzie, because we all know. We just know.

Being Systematic Offers Surprises

Learning what to look for comes with the lovely benefit of enjoying the differences in children.

Recording what children CAN DO, not what they can’t.

Recording what children CAN DO, not what they can’t.

Open boxes invite us to look, not judge.

We grow into getting that hawk eye.

Summer checkmarks.

Fall checkmarks.

Winter checkmarks.

Spring checkmarks.

All 4 together PDF: Allindicators